The

Great Kantō earthquake struck the

Kantō plain on the

Japanese main island of

Honshū at 11:58:44 am JST (2:58:44

UTC) on Saturday, September 1, 1923. Varied accounts indicate the duration of the earthquake was between four and 10 minutes.

This was the deadliest earthquake in Japanese history, and at the time

was the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in the region. The

2011 Tōhoku earthquake later surpassed that record, at magnitude 9.0.

This earthquake devastated

Tokyo, the port city of

Yokohama, and the surrounding prefectures of

Chiba,

Kanagawa, and

Shizuoka, and caused widespread damage throughout the Kantō region. The power was so great in

Kamakura, over 60 km (37 mi) from the epicenter, it moved the

Great Buddha statue, which weighs about 93 short tons (84,000 kg), almost two feet.

Estimated casualties totaled about 142,800 deaths, including about

40,000 who went missing and were presumed dead. The damage from this

natural disaster was the greatest sustained by

prewar Japan. In 1960, the government of Japan declared September 1, the anniversary of the quake, as an annual "Disaster Prevention Day".

According to the Japanese construction company

Kajima Kobori Research's conclusive report of September 2004, 105,385 deaths were confirmed in the 1923 quake.

Damage and deaths

Because the earthquake struck at lunchtime when many people were

cooking meals over fire, many people died as a result of the many large

fires that broke out. Some fires developed into

firestorms that swept across cities. Many people died when their feet became stuck in melting

tarmac. The single greatest loss of life was caused by a firestorm-induced

fire whirl

that engulfed open space at the Rikugun Honjo Hifukusho (formerly the

Army Clothing Depot) in downtown Tokyo, where about 38,000 people were

incinerated after taking shelter there following the earthquake. The

earthquake broke

water mains

all over the city, and putting out the fires took nearly two full days

until late in the morning of September 3. An estimated 140,000 people

were killed and 447,000 houses were destroyed by the fire alone.

A strong

typhoon struck

Tokyo Bay at about the same time as the earthquake. Some scientists, including C.F. Brooks of the

United States Weather Bureau, suggested the opposing energy exerted by a sudden decrease of

atmospheric pressure coupled with a sudden increase of sea pressure by a

storm surge on an already-stressed

earthquake fault, known as the Sagami Trough, may have triggered the earthquake. Winds from the typhoon caused fires off the coast of

Noto Peninsula in

Ishikawa Prefecture to spread rapidly.

The

Emperor and

Empress were staying at

Nikko when the earthquake struck Tokyo, and were never in any danger.

Many homes were buried or swept away by

landslides in the mountainous and hilly coastal areas in western

Kanagawa Prefecture, killing about 800 people. A collapsing mountainside in the village of Nebukawa, west of

Odawara, pushed the entire village and a passenger train carrying over 100 passengers, along with the railway station, into the sea.

A

tsunami with waves up to 10 m (33 ft) high struck the coast of

Sagami Bay,

Boso Peninsula,

Izu Islands, and the east coast of

Izu Peninsula within minutes. The tsunami killed many, including about 100 people along Yui-ga-hama Beach in

Kamakura and an estimated 50 people on the

Enoshima

causeway. Over 570,000 homes were destroyed, leaving an estimated 1.9

million homeless. Evacuees were transported by ship from Kanto to as

far as

Kobe in Kansai. The damage is estimated to have exceeded USD$1 billion (or about $13,475 billion today). There were 57 aftershocks.

Altogether, the earthquake and typhoon killed an estimated 99,300 people, and another 43,500 went missing.

Postquake massacre of ethnic minorities and political opponents

The

Home Ministry declared

martial law, and ordered all sectional police chiefs to make maintenance of order and security a top priority. A rumor spread was that

Koreans were taking advantage of the disaster, committing arson and robbery, and were in possession of bombs.

Anti-Korean sentiment was heightened by fear of the

Korean independence movement, partisans of which were responsible for assassinations of top Japanese officials and other terrorist activity.

In the confusion after the quake, mass murder of Koreans by mobs

occurred in urban Tokyo and Yokohama, fueled by rumors of rebellion and

sabotage.

The government reported 2613 Koreans were killed by mobs in Tokyo and

Yokohama in the first week of September. Independent reports said the

number killed was far higher. Some newspapers reported the rumors as

fact, including the allegation that Koreans were poisoning wells. The

numerous fires and cloudy well water, a little-known effect of a large

quake, all seemed to confirm the rumors of the panic-stricken survivors

who were living amidst the rubble.

Vigilante groups set up roadblocks in cities, and tested residents with a

shibboleth

for supposedly Korean-accented Japanese: deporting, beating, or

killing those who failed. Army and police personnel colluded in the

vigilante killings in some areas. Of the 3,000 Koreans taken into

custody at the Army Cavalry Regiment base in

Narashino, Chiba Prefecture, 10% were killed at the base, or after being released into nearby villages. Moreover, anyone mistakenly identified as Korean, such as Chinese,

Okinawans, and Japanese speakers of some regional dialects, suffered the same fate. About 700 Chinese, mostly from

Wenzhou, were killed. A monument commemorating this was built in 1993 in Wenzhou.

In response, the government called upon the

Japanese Army and the police to detain Koreans to defuse the situation; 23.715 Koreans were detained across Japan, 12.000 in Tokyo alone. The chief of police of

Tsurumi (or

Kawasaki

by some accounts) is reported to have publicly drunk the well water to

disprove the rumor that Koreans had been poisoning wells. In some

towns, even police stations into which Korean people had escaped were

attacked by mobs, whereas in other neighbourhoods, residents took steps

to protect them. The Army distributed flyers denying the rumor and

warning civilians against attacking Koreans, but in many cases

vigilante activity only ceased as a result of Army operations against

it. As Allen notes, the Japanese colonial occupation of Korea provided

the backdrop to this extreme example of the explosion of racial

prejudice into violence, based on a history of antagonism. To be a

Korean in 1923 Japan was to be not only despised, but also threatened

and possibly killed.

Amidst the mob violence against Koreans in the Kantō Region, regional

police and the Imperial Army used the pretext of civil unrest to

liquidate political dissidents.

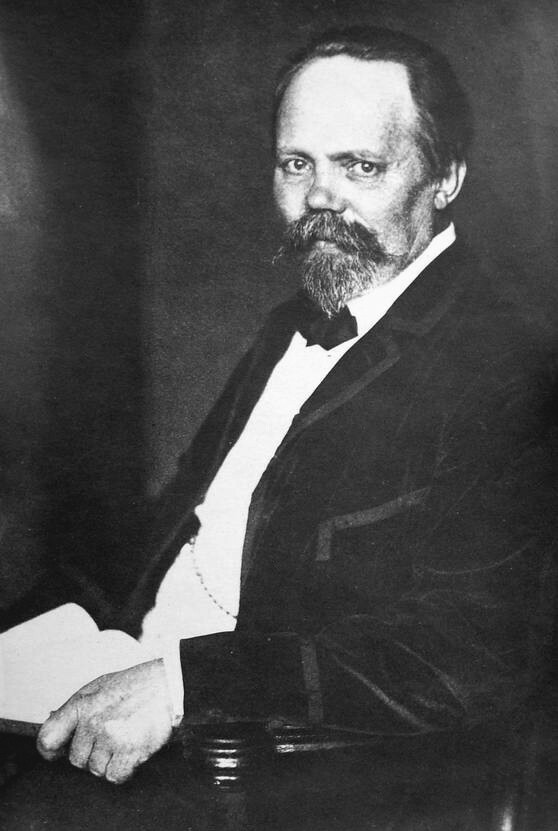

Socialists such as

Hirasawa Keishichi,

anarchists such as

Sakae Osugi and

Noe Ito, and the Chinese communal leader,

Ou Kiten,

were abducted and killed by local police and Imperial Army, who

claimed the radicals intended to use the crisis as an opportunity to

overthrow the Japanese government.

The importance of obtaining and providing accurate information

following natural disasters has been emphasized in Japan ever since.

Earthquake preparation literature in modern Japan almost always directs

citizens to carry a portable radio and use it to listen to reliable

information, and not to be misled by rumors in the event of a large

earthquake.

Aftermath

Following the devastation of the earthquake, some in the government considered the possibility of moving the capital elsewhere. Proposed sites for the new capital were even discussed.

Japanese commentators interpreted the disaster as an act of divine (

Kami)

punishment to admonish the Japanese people for their self-centered,

immoral, and extravagant lifestyles. In the long run, the response to

the disaster was a strong sense that Japan had been given an

unparalleled opportunity to rebuild the city, and to rebuild Japanese

values. In reconstructing the city, the nation, and the Japanese people,

the earthquake fostered a culture of catastrophe and reconstruction

that amplified discourses of moral degeneracy and national renovation in

interwar Japan.

After the earthquake,

Gotō Shimpei organized a reconstruction plan of Tokyo with modern networks of

roads,

trains, and public services.

Parks

were placed all over Tokyo as refuge spots, and public buildings were

constructed with stricter standards than private buildings to

accommodate refugees. However, the outbreak of

World War II and subsequent destruction severely limited resources.

Frank Lloyd Wright received credit for designing the

Imperial Hotel, Tokyo,

to withstand the quake, although in fact the building was damaged by

the shock. The destruction of the US embassy caused Ambassador

Cyrus Woods to relocate the embassy to the hotel. Wright's structure withstood the anticipated earthquake stresses, and the hotel remained in use until 1968.

The unfinished

battlecruiser Amagi was in drydock being converted into an

aircraft carrier in

Yokosuka in compliance with the

Washington Naval Treaty of 1922. However, the earthquake damaged the

Amagi beyond repair, leading it to be scrapped, and the unfinished fast battleship

Kaga was converted into an aircraft carrier in its place.

In contrast to London, where typhoid fever had been steadily declining

since the 1870s, the rate in Tokyo remained high, more so in the

upper-class residential northern and western districts than in the

densely populated working-class eastern district. An explanation is the

decline of waste disposal, which became particularly serious in the

northern and western districts when traditional methods of waste

disposal collapsed due to urbanization. The 1923 earthquake led to

record-high morbidity due to unsanitary conditions following the

earthquake, and it prompted the establishment of antityphoid measures

and the building of urban infrastructure.

Memory

Beginning in 1960, every September 1 is designated as

Disaster Prevention Day

to commemorate the earthquake and remind people of the importance of

preparation, as September and October are the middle of the typhoon

season. Schools and public and private organizations host disaster

drills. Tokyo is located near a

fault zone beneath the

Izu peninsula

which, on average, causes a major earthquake about once every 70 years,

and is also located near the Sagami Trough, a large subduction zone

that threatens to create a massive earthquake that, in the darkest case,

would kill millions in the Kanto Region. Every year on this date,

schools across Japan take a moment of silence at the precise time the

earthquake hit in memory of the lives lost.

Some discreet memorials are located in

Yokoamicho Park in

Sumida Ward,

at the site of the open space in which an estimated 38,000 people were

killed by a single firestorm. The park houses a Buddhist-style

memorial hall/museum, a memorial bell donated by Taiwanese Buddhists, a

memorial to the victims of

World War II Tokyo air raids, and a memorial to the Korean victims of the vigilante killings.