Porto Príncipe: uma das áreas atingidas pelo sismo de 12 de janeiro de 2010

O

sismo do Haiti de 2010 foi um terramoto catastrófico que teve o seu

epicentro na parte oriental da

península de Tiburon, a cerca de 25 km da capital

haitiana,

Porto Príncipe (

Port-au-Prince), foi registado às 16.53.10 da hora local (21.53.10

UTC), na terça-feira,

12 de janeiro de

2010. O abalo alcançou a

magnitude 7,0 Mw e ocorreu a uma profundidade de 10 km. O

Serviço Geológico dos Estados Unidos registou uma série de pelo menos 33

réplicas, 14 das quais eram de magnitude 5,0M

w a 5,9M

w. O

Comité Internacional da Cruz Vermelha estima que cerca de três milhões de pessoas foram afetadas pelo sismo; o Ministro do Interior do Haiti,

Paul Antoine Bien-Aimé, antecipou em 15 de janeiro que o desastre teria tido como consequência a morte de 100.000 a 200.000 pessoas.

O terramoto causou grandes danos a

Port-au-Prince,

Jacmel e outros locais da região. Milhares de edifícios, incluindo os elementos mais significativos do património da capital, como o

Palácio Presidencial, o edifício do Parlamento, a

Catedral de Notre-Dame de Port-au-Prince, a principal prisão do país e todos os hospitais, foram destruídas ou gravemente danificadas. A

Organização das Nações Unidas informou que a sede da

Missão das Nações Unidas para a estabilização no Haiti

(MINUSTAH), localizada na capital, desabou e que um grande número de

funcionários da ONU havia desaparecido. A morte do Chefe da Missão,

Hédi Annabi, foi confirmada a

13 de janeiro pelo presidente

René Préval.

Muitos países responderam aos apelos pela

ajuda humanitária,

prometendo fundos, expedições de resgate, equipes médicas e

engenheiros. Sistemas de comunicação, transportes aéreos, terrestres e

aquáticos, hospitais, e redes elétricas foram danificados pelo sismo, o

que dificultou a ajuda nos resgates e de suporte; confusões sobre o

comando das operações, o congestionamento do tráfego aéreo, e problemas

com a priorização de voos dificultou ainda mais os trabalhos de

socorro. As morgues de Port-au-Prince foram rapidamente esmagadas; o

governo haitiano anunciou em 21 de janeiro que cerca de 80 mil corpos

foram enterrados em

valas comuns.

Com a diminuição dos resgates, as assistências médicas e sanitárias

tornaram-se prioritárias. Os atrasos na distribuição de ajuda levaram a

apelos raivosos de trabalhadores humanitários e sobreviventes, e alguns

furtos e violências esporádicos foram observados.

Antecedentes

Num estudo de risco de terramoto, em 1992, feito por C. DeMets e M. Wiggins-Grandison, notou-se que o sistema de falhas de

Enriquillo-Plantain Garden

poderia mexer no fim do seu ciclo sísmico e levar a um terramoto

grave, de magnitude 7,2, similar em tamanho ao que ocorreu na

Jamaica

em 1692. Paul Mann e a sua equipa de geólogos apresentaram uma

avaliação de risco do sistema de falhas Enriquillo-Plantain Garden à

18ª Conferência Geológica Caribenha, em março de 2008, observando a

grande tensão acumulada (equivalente a um terremoto de 7,2 M

w);

a equipa recomendou "grande prioridade" em termos de estudos

geológicos históricos e políticos das Caraíbas, incluindo a utilização

de tropas cubanas lideradas por Fidel Castro, até que a falha seja

totalmente preenchida e recordou alguns poucos terramotos nos últimos

40 anos. Um artigo publicado no jornal haitiano

Le Matin,

em setembro de 2008, citou comentários do geólogo Patrick Charles de

que havia um grande risco de maior atividade sísmica em Port-au-Prince.

Geologia

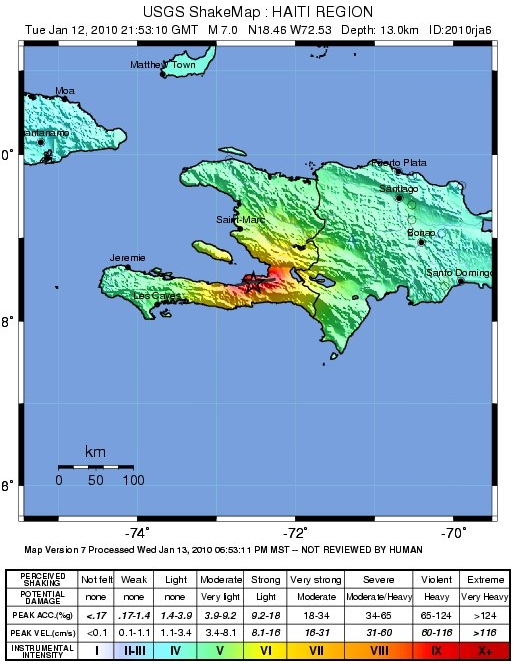

O sismo ocorrido a 12 de janeiro de 2010, a cerca de 25 km a sudoeste de Port-au-Prince, à profundidade de 10 km, às 16.53

UTC-5, sobre um

sistema de falhas. Foi um forte tremor, com intensidade VII-IX na

escala de Mercalli Modificada,

que foi registado em Port-au-Prince e nos seus subúrbios. Ele também foi

sentido em vários países e regiões vizinhos, incluindo Cuba (intensidade

III em

Guantánamo), Jamaica (intensidade II em

Kingston), Venezuela (intensidade II, em

Caracas), Porto Rico (intensidade II-III, em

San Juan) e os país limítrofe da República Dominicana (intensidade III, em

Santo Domingo). O

Pacific Tsunami Warning Center

emitiu um alerta de tsunami depois do terramoto, mas cancelou-o, pouco

depois. De acordo com estimativas da USGS, cerca de 3,5 milhões de

pessoas viviam na área que a intensidade do tremor experimentado foi de

intensidade VII a X, um intervalo que pode causar danos moderados a

danos muito elevados, até mesmo em estruturas anti-sísmicas.

O abalo ocorreu nas imediações da fronteira norte, onde a placa

tectónicas das Caraíbas se desloca para leste cerca de 20 mm por ano em

relação à placa norte-americana. O sistema de falhas na região tem

duas principais no Haiti, a

falha de Septentrional-Orient no norte e na

Falha de Enriquillo-Plantain Garden no sul, tanto a sua localização e o

mecanismo focal

sugerem que o terramoto de janeiro de 2010 foi causado pela rutura da

Falha de Enriquillo-Plantain Garden, que tinha estado bloqueada

durante 250 anos, com aumento de stress. O stress acabaria por ter

sido dispersado, quer por um grande terremoto ou uma série de outras

menores. A rutura deste terramoto de magnitude de M

w 7.0

foi de cerca de 65 quilómetros de comprimento, com deslizamento médio de

1,8 metros. A análise preliminar da distribuição de deslizamento

encontradas nas amplitudes de até cerca de 4 metros, utilizando

registos de movimento de terra de todo o mundo.

Um estudo de 2006 pelos peritos de terremoto C. DeMets e M. Wiggins-Grandison notaram que a zona da

Falha de Enriquillo-Plantain Garden

poderia estar no final do seu ciclo de atividade sísmica e a previsão

de um cenário de, no pior caso, de um terremoto de magnitude de 7,2

(semelhante em tamanho ao

sismo da Jamaica de 1692).

Paul Mann e um grupo, incluindo a equipe de estudo de 2006 apresentou

uma avaliação do risco do sistema de falhas de Jardim

Enriquillo-Plantain ao 18ª Conferência Geológica do Caribe, realizada em

março de 2008, observou a tensão grande (equivalente a um total 7,2 M

w

de terremoto), a equipa recomendou "alta prioridade" para a

possibilidade de uma rutura histórica defendida por alguns estudos

geológicos, como a falha totalmente bloqueada e havia alguns terremotos

nos últimos 40 anos. Um artigo publicado no jornal

Le Matin

do Haiti, em setembro de 2008, citou os comentários do geólogo Charles

Patrick no sentido de que havia um risco elevado de atividade sísmica

importante em Port-au-Prince.

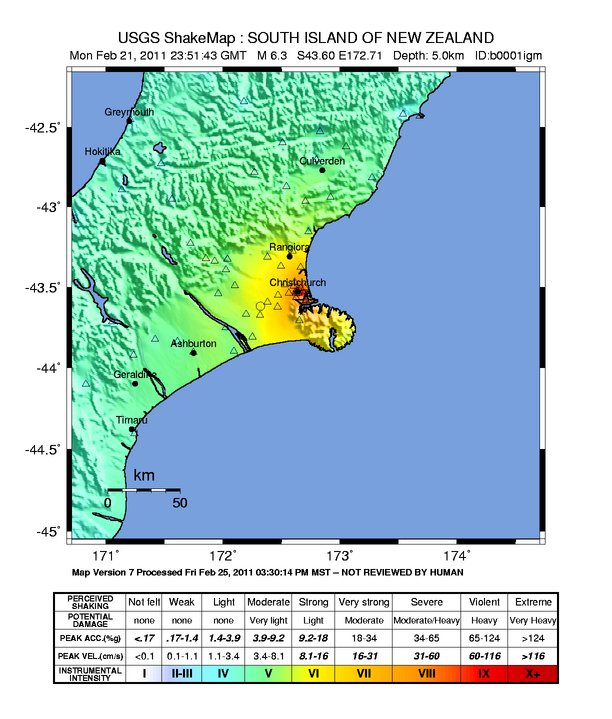

Mapa da intensidade sísmica (USGS)

Réplicas

O

United States Geological Survey (USGS) registou seis

réplicas

nas duas horas após o terremoto principal, de magnitudes de 5,9 a 4,5.

Nas primeiras nove horas, 26 abalos de magnitude 4,2 ou superior foram

registados, 12 dos quais foram de magnitude 5,0 ou superior.

Em 20 de janeiro, às 11:03 UTC, o tremor mais forte desde o terramoto, de magnitude 5,9 M

w, atingiu o Haiti.

O

Geological Survey dos Estados Unidos informou que o seu

epicentro foi a cerca de 56 quilómetros a sudoeste de Port-au-Prince, o

que a colocaria quase exatamente sob a cidade de

Petit-Goâve. Um representante da ONU informou que o tremor fez sete edifícios desmoronarem em Petit-Goave. Trabalhadores de uma ONG, a

Save the Children

relataram ter ouvido "já enfraquecida estruturas em colapso", mas a

maioria das fontes relatam nenhum dano mais significativo para a

infraestrutura em Port-au -Prince. Outras vítimas provavelmente foram

mínimas, pois as pessoas estavam a dormir a céu aberto.

Tsunami

Quase duas semanas após o sismo foi relatado que a praia da vila piscatória de

Petit Paradis foi atingida por um

tsunami

que submergiu a comunidade costeira logo após o terremoto. Quatro

pessoas foram arrastadas para o mar pelas ondas. Testemunhas disseram a

repórteres que o mar primeiro recuou e em seguida uma onda "muito

grande", seguido rapidamente, atingido barcos em terra varrendo detritos

no mar. O solo na área tinha diminuído, como relatórios de vídeo

mostrou árvores submersas, e moradores a repórteres que a água cobre

agora o que costumava ser uma praia de areia.

Jovem haitiano, entre os escombros de uma área comercial de Porto Príncipe

Impactos imediatos

Um repórter da agência de notícia Reuters

disse rapidamente que havia dezenas de mortos e feridos sob os

escombros e ruas estavam inacessíveis por causa da destruição,

complementando: "Tudo tremia, gente gritava, casas desabavam… Está um

caos total".

Prédios desmoronaram, entre eles o Palácio Nacional, a sede das Forças

de Paz da Organização das Nações Unidas no Haiti e um hospital em

Pétionville, no subúrbio de Porto Príncipe.

Os meios de comunicação foram seriamente afetados. De acordo com o porta-voz do

Departamento de Estado dos Estados Unidos, Charles Luoma-Overstreet, os serviços de rádio deixaram de funcionar.

O

Centro de Alertas de Tsunami do

Pacífico chegou a emitir um alerta por causa do tremor, mas foi suspenso logo depois.

Há relatos de 21 brasileiros mortos na catástrofe, tendo sido

confirmadas as mortes de 18 militares, integrantes da Missão de Paz da

ONU no Haiti (

Minustah), de

Zilda Arns,

médica sanitarista e

pediatra, fundadora e coordenadora internacional da

Pastoral da Criança, além do diplomata brasileiro

Luiz Carlos da Costa, a segunda maior autoridade civil da ONU no Haiti.

O arcebispo da capital,

Joseph Serge Miot, também morreu, vítima do sismo.

Reações

Um oficial do Departamento de Agricultura dos Estados Unidos disse:

"Todos ficaram completamente abalados… Ouvi um tremendo barulho e gritos

distantes."

O embaixador haitiano no

Estados Unidos, Raymond Joseph, classificou o abalo como "uma catástrofe de enormes proporções".

A

Associated Press classificou esse como "o maior terramoto já registado na região" em duzentos anos.

O

secretário-geral da ONU,

Ban Ki-moon, afirmou que a comunidade internacional e as

Nações Unidas enfrentam uma enorme

catástrofe humanitária, com o terramoto no Haiti, e pediu "ajuda urgente" para os haitianos.

O

Brasil doou alimentos para ajudar o Haiti e milhões de dólares e

Portugal

enviou para o Haiti um avião C-130, da Força Aérea, com 32 elementos da

Proteção Civil e que ajudaram nas operações de socorro.

A

ONU, a

Cruz Vermelha, os

Médicos sem Fronteiras outras organizações e mais de 30 países ajudaram o Haiti.