| Date | December 28, 1908 5:20 am |

|---|---|

| Magnitude | 7.1 Mw |

| Epicenter | 38.15°N 15.683°E |

| Areas affected | Sicily & Calabria, Italy |

| Tsunami | Yes |

| Casualties | 100.000 to 200.000 |

O Curso de Geologia de 85/90 da Universidade de Coimbra escolheu o nome de Geopedrados quando participou na Queima das Fitas. Ficou a designação, ficaram muitas pessoas com e sobre a capa intemporal deste nome, agora com oportunidade de partilhar as suas ideias, informações e materiais sobre Geologia, Paleontologia, Mineralogia, Vulcanologia/Sismologia, Ambiente, Energia, Biologia, Astronomia, Ensino, Fotografia, Humor, Música, Cultura, Coimbra e AAC, para fins de ensino e educação.

| Date | December 28, 1908 5:20 am |

|---|---|

| Magnitude | 7.1 Mw |

| Epicenter | 38.15°N 15.683°E |

| Areas affected | Sicily & Calabria, Italy |

| Tsunami | Yes |

| Casualties | 100.000 to 200.000 |

Postado por

Fernando Martins

às

01:15

0

bocas

![]()

Marcadores: Calábria, Itália, Sicília, sismo, Sismo de Messina, sismologia, tsunami

Postado por

Fernando Martins

às

00:20

0

bocas

![]()

Marcadores: Bam, Irão, sismo, Sismo de Bam de 2003, sismologia

After supper, we went to sleep as usual: about ten o'clock, and in the night I was awakened by the most tremendous noise, accompanied by an agitation of the boat so violent, that it appeared in danger of upsetting ... I could distinctly see the river as if agitated by a storm; and although the noise was inconceivably loud and terrific, I could distinctly hear the crash of falling trees, and the screaming of the wild fowl on the river, but found that the boat was still safe at her moorings.

By the time we could get to our fire, which was on a large flag in the stern of the boat, the shock had ceased; but immediately the perpendicular banks, both above and below us, began to fall into the river in such vast masses, as nearly to sink our boat by the swell they occasioned ... At day-light we had counted twenty-seven shocks.

On the 16th of December, 1811, about two o'clock, a.m., we were visited by a violent shock of an earthquake, accompanied by a very awful noise resembling loud but distant thunder, but more hoarse and vibrating, which was followed in a few minutes by the complete saturation of the atmosphere, with sulphurious vapor, causing total darkness. The screams of the affrighted inhabitants running to and fro, not knowing where to go, or what to do—the cries of the fowls and beasts of every species—the cracking of trees falling, and the roaring of the Mississippi— the current of which was retrograde for a few minutes, owing as is supposed, to an irruption in its bed— formed a scene truly horrible.

On the night of 16th November [sic], 1811, an earthquake occurred, that produced great consternation amongst the people. The centre of the violence was in New Madrid, Missouri, but the whole valley of the Mississippi was violently agitated. Our family all were sleeping in a log cabin, and my father leaped out of bed crying aloud "the Indians are on the house" ... We laughed at the mistake of my father, but soon found out it was worse than the Indians. Not one in the family knew at the time that it was an earthquake. The next morning another shock made us acquainted with it, so we decided it was an earthquake. The cattle came running home bellowing with fear, and all animals were terribly alarmed on the occasion. Our house cracked and quivered, so we were fearful it would fall to the ground. In the American Bottom many chimneys were thrown down, and the church bell in Cahokia sounded by the agitation of the building. It is said the shock of an earthquake was felt in Kaskaskia in 1804, but I did not perceive it. The shocks continued for years in Illinois, and some have experienced it this year, 1855.

Postado por

Fernando Martins

às

02:12

0

bocas

![]()

Marcadores: crise sísmica, New Madrid, sismo, sismologia, USA

| Rank | Date | Location | Event | Magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | May 22, 1960 | 1960 Valdivia earthquake | 9.4–9.6 | |

| 2 | June 11, 1585 | 1585 Aleutian Islands earthquake | 9.25 (est.) | |

| 3 | July 8, 1730 | 1730 Valparaíso earthquake | 9.1–9.3 (est.) | |

| 4 | March 27, 1964 | 1964 Alaska earthquake | 9.2 | |

| 5 | December 26, 2004 | 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake | 9.1–9.3 | |

| 6 | October 17, 1737 | 1737 Kamchatka earthquake | 9.0–9.3 (est.) | |

| 7 | November 17, 1837 | 1837 Valdivia earthquake | 8.8–9.5 (est.) | |

| 8 | March 11, 2011 | 2011 Tōhoku earthquake | 9.1 | |

| 9 | October 28, 1707 | 1707 Hōei earthquake | 8.7–9.3 (est.) | |

| 10 | November 25, 1833 | 1833 Sumatra earthquake | 8.8–9.2 (est.) | |

| 11 | May 17, 1841 | 1841 Kamchatka earthquake | 9.0 (est.) | |

| 12 | November 4, 1952 | 1952 Severo-Kurilsk earthquake | 9.0 |

Postado por

Fernando Martins

às

07:10

0

bocas

![]()

Marcadores: Anel de Fogo do Pacífico, Kamchatka, Rússia, sismo, sismologia, tsunami

Postado por

Fernando Martins

às

00:35

0

bocas

![]()

Marcadores: Califórnia, falha de Santo André, Loma Prieta, São Francisco, sismo, sismologia, USA

| Date | 11:40:26, September 26, 1997 (UTC) |

|---|---|

| Magnitude | 6.1 Mw |

| Depth | 10 km (6.2 mi) |

| Epicenter | 43.084°N 12.812°E |

| Countries or regions | Italy (Umbria, Marche) |

| Casualties | 11 dead 100 injured |

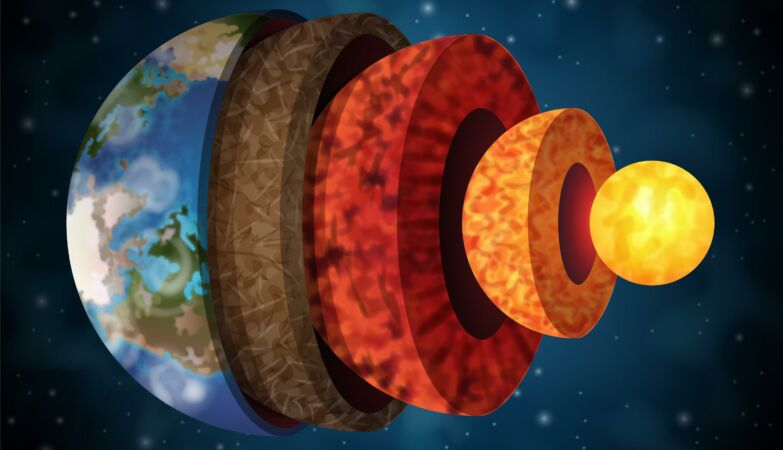

Por que o núcleo da Terra é mais quente que a superfície do Sol, mas é sólido?

Apesar de ser mais quente do que a superfície do sol, o núcleo interno da Terra é sólido devido à imensa pressão exercida pelas sucessivas camadas superiores no interior do planeta.

O núcleo da Terra, uma esfera metálica com aproximadamente 2.400 quilómetros de largura, está sujeito a pressões de cerca de 350 gigapascais, equivalentes a mais de três milhões de vezes a pressão atmosférica ao nível do mar.

Esta colossal pressão é suficiente para converter uma mistura de ferro, níquel e outros elementos de líquido para sólido.

Os cientistas descobriram que a temperatura na superfície do núcleo interno da Terra é de 5.700 a 6.200 ºC.

O facto de o núcleo interno da Terra ser sólido pode parecer contraditório, uma vez que os materiais, a altas temperaturas, geralmente passam de estado sólido para líquido, e de líquido para gasoso.

No entanto, da mesma forma como a água ferve a temperaturas mais baixas em altitudes mais elevadas devido à redução da pressão do ar, a pressão aumentada pode elevar a temperatura à qual uma substância funde, explica o IFLS.

Os cientistas determinam a temperatura na fronteira do núcleo interno sólido e do núcleo externo líquido calculando a pressão nesse ponto e estimando quão quentes os metais do núcleo podem ser, mantendo-se ainda sólidos.

Devido à falta de medições diretas, estas estimativas variam, mas uma desvio de 10% é considerado insignificante ao lidar com condições tão extremas.

Além disso, especula-se que o núcleo interno está a expandir-se lentamente, porque o núcleo está gradualmente a arrefecer à medida que a concentração de elementos radioativos que o aquecem diminui, fazendo com que partes do núcleo externo solidifiquem.

No entanto, não é absolutamente certo que o núcleo interno seja verdadeiramente sólido, devido à semelhança na forma como as vibrações viajam através de sólidos e líquidos extremamente viscosos.

Alguns cientistas avançam a hipótese de que, se o núcleo interno for de facto um líquido altamente viscoso.

Essa viscosidade poderia contribuir para o campo magnético do planeta e explicar por que motivo as ondas sísmicas demoram mais tempo a viajar, pelo interior da Terra, nas regiões equatoriais do que nas regiões polares.

Postado por

Fernando Martins

às

19:45

0

bocas

![]()

Marcadores: Núcleo, planetologia, sismologia, Terra

Houve três sismos, dois no Algarve e um no Alentejo, sentidos pela população local, só no dia de hoje (5 de setembro de 2023)...

Aqui fica um mapa do IPMA com o mais forte desses sismos (intensidade IV):

Para quem sentiu algum dos sismos, uma sugestão - vão ao seguinte link e respondam ao inquérito on line do IPMA:

https://www.ipma.pt/pt/geofisica/informe/

ADENDA: houve mais um sismo sentido em Portugal continental no dia de hoje, que nos fez alterar o título da publicação - desta vez o sismo foi perto de Castro Daire e São Pedro do Sul...! É provavelmente um record nacional - quase que chegamos aos Açores.

Postado por

Fernando Martins

às

00:01

0

bocas

![]()

Marcadores: Disaster Prevention Day, Grande Sismo de Kanto, Honshu, Japão, sismo, sismologia, Tóquio, Yokohama

Postado por

Fernando Martins

às

16:20

0

bocas

![]()

Marcadores: astronomia, Herbert Hall Turner, hipocentro, parsec, sismologia

Placas tectónicas a “escamar” podem explicar mistério de terramotos em Portugal

Epicentro do terramoto de 1969

Investigadores suspeitam que o “descasque” de uma placa tectónica possa ter estado na origem dos terramotos de 1755 e 1969 que fustigaram Lisboa.

Sempre que um terramoto de magnitudes mais significativas acontece (como o que fustigou a Turquia e a Síria, no início de fevereiro), a possibilidade de um evento semelhante acontecer em Portugal é abordada pelos meios de comunicação.

Os especialistas são unânimes nos contributos, devido à sua localização, o país (sobretudo a zona sul) está particularmente exposto a um sismo de grandes dimensões. Já aconteceu no passado, não há motivo para acreditar que não se vai repetir.

Os especialistas têm estado atentos, pelo que já notaram um fenómeno estranho que está a acontecer ao largo da costa portuguesa, mas nas profundezas do oceano Atlântico. Uma placa tectónica está a descascar, criando uma nova “zona de subducção” que um dia pode vir a tornar-se um foco de atividade sísmica e vulcânica.

A descoberta representa a primeira do seu tipo, pelo menos nesta fase de “descasque”, e está a ser apontada como causa provável para o terramoto de 1755 e para outro de dimensões mais pequenas que se registou em 1969.

Apesar das condições favoráveis, os cientistas nunca conseguiram designar uma causa clara para os dois eventos, lembra João Duarte, geólogo da Universidade de Lisboa, citado pela NBC News.

A crosta terrestre é constituída por várias placas tectónicas, ou seja, placas rochosas de forma irregular que chocam, sobem ou deslizam umas por baixo das outras à medida que se movimentam lenta mas continuamente.

Os sismos, assim como as erupções vulcânicas, tendem a agrupar-se nas zonas de subducção, as quais ocorrem ao longo dos limites entre as placas quando uma é empurrada para baixo de outra.

O terramoto de Lisboa, sentido a 1 de novembro de 1755, atingiu grande parte da cidade, provocou um tsunami e causou até 100.000 mortes.

Na altura, os sismógrafos não existiam, mas os cientistas estimam que foi um sismo de magnitude 8,5 a 8,7. Mais de dois séculos depois, a 28 de fevereiro de 1969, um terramoto de magnitude 7,8 atingiu a mesma área.

Para compreender o que poderia ter estado na origem dos sismos, João Duarte e os seus colegas analisaram dados sísmicos recolhidos em 2007 e 2008 a partir de ferramentas colocados no fundo do mar, os quais foram cruzados com dados de outros dois estudos.

Essas pesquisas detetaram uma estranha região densa a 240 quilómetros abaixo do epicentro do sismo de 1969.

O investigador vê nos dados a prova de que é a prova de que a água do mar está lentamente a infiltrar-se na placa tectónica através de uma série de fissuras, enfraquecendo a sua estrutura geral e fazendo com que a parte inferior da placa se afaste do topo.

O processo pode ter começado há cerca de 10 milhões de anos, apontou, acrescentando que a modelagem por computador confirmou o processo como uma possibilidade provável.

“Por vezes, penso no fenómeno como uma zona de subducção embrionária“, disse Duarte. “Ainda não está totalmente madura, mas as condições estão todas lá”.

in ZAP

Postado por

Fernando Martins

às

11:11

0

bocas

![]()

Marcadores: sismo de 1755, sismologia, subdução, Tectónica de Placas

Postado por

Fernando Martins

às

00:47

0

bocas

![]()

Marcadores: China, Grande Sismo de Tangshan, previsão de sismos, revolução cultural, sismologia

El terremoto se inició el 31 de mayo de 1970 de 7,9 a las 3:25 p.m. Su epicentro se halló frente a las costas de las ciudades de Casma y Chimbote, en el Océano Pacífico. Su magnitud fue de 7,8 grados en la escala de Richter y alcanzó una intensidad de hasta X y XI grados en la escala de Mercalli entre Chimbote y Casma. Produjo además un violento alud en las ciudades de Yungay y Ranrahirca.

Efectos en el Callejón de Huaylas y el Perú

Las muertes se calcularon en 80.000 y hubo aproximadamente de 20.000 desaparecidos, algunas fuentes elevan las víctimas mucho más alto. Los heridos hospitalizados se contabilizaron en 143.331, si bien en lugares como Recuay, Aija, Casma, Huarmey, Carhuaz y Chimbote la destrucción de edificios osciló entre 80% y 90%. Se calculó el número de afectados en 3.000.000. La Carretera Panamericana sufrió graves grietas entre Trujillo y Huarmey, lo que dificultó aún más la entrega de ayuda. La central hidroeléctrica del Cañón del Pato quedó también afectada por el embate del río Santa y la línea férrea que comunicaba Chimbote con el valle del Santa y quedó inutilizable en un 60% de su recorrido. Con esta catástrofe el Perú sacó volutariamente a la Brigada de Defensa Civil Peruana para evitar que vuelva a suceder algo tan terrible; el general Juan Velasco Alvarado, que era el presidente del país en ese entonces, tomó un barco para llevar personalmente la ayuda a Chimbote.

«...Sentimos un tremendo ruido que se presentaba de ambos lados... el ruido se asemejaba al de muchos aviones... no sabíamos por donde venía ni que pasaba, en esos momentos no nos acordábamos del Huascarán... Finalmente vimos el aluvión de lodo completamente negro con más de 400 metros de altura que avanzaba botando chispas de distintos colores...»En Yungay sólo se salvaron aproximadamente 300 personas separadas en dos grupos, 90 personas que corrieron hacia el cementerio de la ciudad (una antigua fortaleza preinca elevada), y un numeroso grupo de niños que asistieron a un circo itinerante llamado Verolina y que estaba ubicado en el estadio a 700 metros de la plaza mayor.

Relato de una superviviente, en 1970

Postado por

Fernando Martins

às

00:53

0

bocas

![]()

Marcadores: Áncash, deslizamento, Peru, sismo, sismologia, Yungay