Carbonaceous chondrites comprise about 4 percent of all meteorites observed to fall from space. Prior to 1969, the carbonaceous chondrite class was known from a small number of uncommon meteorites such as

Orgueil, which fell in France in 1864. Meteorites similar to Allende were known, but many were small and poorly studied.

Fall

The original stone is believed to have been approximately the size of an automobile traveling towards the Earth at more than 10 miles per second. The fall occurred in the early morning hours of February 8, 1969. At 01:05 a huge, brilliant

fireball approached from the southwest and lit the sky and ground for hundreds of miles. It exploded and broke up to produce thousands of fusion crusted individuals. This is typical of falls of large stones through the atmosphere and is due to the sudden braking effect of air resistance. The fall took place in northern Mexico, near the village of Pueblito de Allende in the state of Chihuahua. Allende stones became one of the most widely distributed meteorites and provided a large amount of material to study, far more than all of the previously known carbonaceous chondrite falls combined.

Path of the fireball and the area in northern Mexico where the meteorite pieces landed (the strewnfield)

Strewnfield

Stones were scattered over a huge area – one of the largest meteorite

strewnfields known. This strewnfield measures approximately 8 by 50 kilometers. The region is desert, mostly flat, with sparse to moderate low vegetation. Hundreds of meteorites were collected shortly after the fall. Approximately 2 or 3 tonnes of specimens were collected over a period of more than 25 years. Some sources guess that an even larger amount was recovered (estimates as high as 5 tonnes can be found), but there is no way to make an accurate estimate. Even today, over 40 years later, specimens are still occasionally found. Fusion crusted individual Allende specimens ranged from 1 gram to 110 kilograms.

Study

Allende is often called "the best-studied meteorite in history." There are several reasons for this: Allende fell in early 1969, just months before the

Apollo program was to return the first moon rocks. This was a time of great excitement and energy among planetary scientists. The field was attracting many new workers and laboratories were being improved. As a result, the scientific community was immediately ready to study the new meteorite. A number of museums launched expeditions to Mexico to collect samples, including the

Smithsonian Institution and together they collected hundreds of kilograms of material with

CAls. The CAls are billions of years old, and help to determine the age of the solar system. The CAls had very unusual

isotopic compositions, with many being distinct from the Earth, Moon and other meteorites for a wide variety of isotopes. These "isotope anomalies" contain evidence for processes that occurred in other stars before the solar system formed.

Allende contains chondrules and CAls that are estimated to be 4.567 billion years old,

the oldest known matter (other carbonaceous chondrites also contain these). This material is 30 million years older than the Earth and 287 million years older than the

oldest rock known on Earth, Thus, the Allende meteorite has revealed information about conditions prevailing during the early formation of our solar system. Carbonaceous chondrites, including Allende, are the most primitive meteorites, and contain the most primitive known matter. They have undergone the least mixing and remelting since the early stages of solar system formation. Because of this, their age is frequently taken as the "age of the solar system."

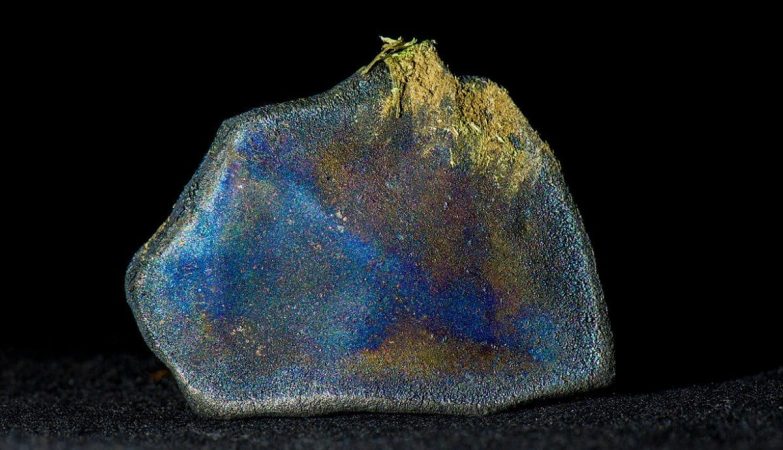

Allende meteorite - image by Matteo Chinellato; cube = 1 cm

Structure

The meteorite was formed from nebular dust and gas during the early formation of the solar system. It is a "stone" meteorite, as opposed to an "iron," or "stony iron," the other two general classes of meteorite. Most Allende stones are covered, in part or in whole, by a black, shiny crust created as the stone descended at great speed through the atmosphere as it was falling towards the earth from space. This causes the exterior of the stone to become very hot, melting it, and forming a glassy "fusion crust."

When an Allende stone is sawed into two pieces and the surface is polished, the structure in the interior can be examined. This reveals a dark matrix embedded throughout with mm-sized, lighter-colored

chondrules, tiny stony spherules found only in meteorites and not in earth rock (thus it is a

chondritic meteorite). Also seen are white inclusions, up to several cm in size, ranging in shape from spherical to highly irregular or "amoeboidal." These are known as

calcium-aluminum-rich inclusions or "CAls", so named because they are dominantly composed of calcium- and aluminum-rich

silicate and

oxide minerals. Like many chondrites, Allende is a

breccia, and contains many dark-colored clasts or "dark inclusions" which have a chondritic structure that is distinct from the rest of the meteorite. Unlike many other chondrites, Allende is almost completely lacking in Fe-Ni

metal.

Composition

The matrix and the

chondrules consist of many different minerals, predominantly

olivine and

pyroxene. Allende is classified as a CV3 carbonaceous chondrite: the chemical composition, which is rich in

refractory elements like calcium, aluminum, and titanium, and poor in relatively

volatile elements like sodium and potassium, places it in the CV group, and the lack of secondary heating effects is consistent with petrologic type 3 (see

meteorites classification). Like most carbonaceous chondrites and all CV chondrites, Allende is enriched in the oxygen

isotope O-16 relative to the less abundant isotopes, O-17 and O-18. In June 2012, researchers announced the discovery of another inclusion dubbed

panguite, a hitherto unknown type of titanium dioxide mineral.

There was found to be a small amount of carbon (including graphite and diamond), and many organic compounds, including amino acids, some not known on Earth. Iron, mostly combined, makes up about 24% of the meteorite.

Subsequent reserch

Close examination of the chondrules in 1971, by a team from

Case Western Reserve University, revealed tiny black markings, up to 10 trillion per square centimeter, which were absent from the matrix and interpreted as evidence of radiation damage. Similar structures have turned up in

lunar basalts but not in their terrestrial equivalent which would have been screened from cosmic radiation by the Earth's atmosphere and geomagnetic field. Thus it appears that the irradiation of the chondrules happened after they had solidified but before the cold accretion of matter that took place during the early stages of formation of the solar system, when the parent meteorite came together.

The discovery at

California Institute of Technology in 1977 of new forms of the elements

calcium,

barium and

neodymium in the meteorite was believed to show that those elements came from some source outside the early clouds of gas and dust that formed the solar system. This supports the theory that shockwaves from a

supernova - the explosion of an aging star - may have triggered the formation of, or contributed to the formation of our solar system. As further evidence, the Caltech group said the meteorite contained

Aluminum 26, a rare form of aluminum. This acts as a "clock" on the meteorite, dating the explosion of the supernova to within less than 2 million years before the solar system was formed.

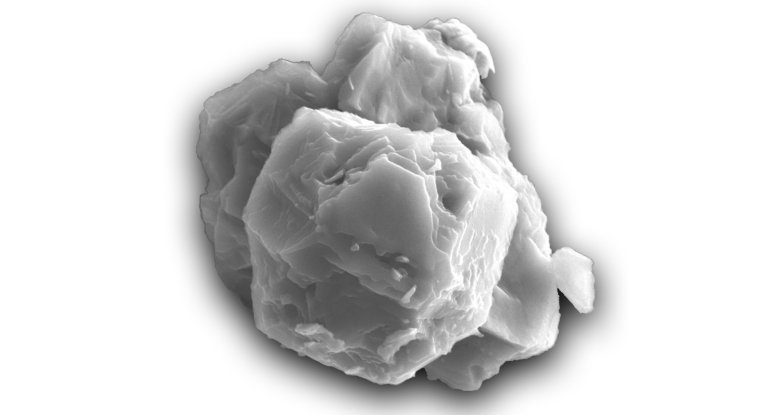

Subsequent studies have found isotopic ratios of

krypton,

xenon,

nitrogen and other elements that are also unknown in our solar system. The conclusion, from many studies with similar findings, is that there were a lot of substances in the presolar disc that were introduced as fine "dust" from nearby stars, including novas, supernovas, and

red giants. These specks persist to this day in meteorites like Allende, and are known as

presolar grains.