O estranho asteroide 3200 Phaeton acabou de ficar um pouco menos estranho

Asteroide 3200 Phaethon

Uma equipa de investigadores finlandeses descobriu a composição

do 3200 Faetonte, o estranho asteroide que mais parece um cometa.

O asteroide 3200 Faetonte (3200 Phaethon, em inglês), que tem 5 km de diâmetro, há muito que intriga os investigadores.

Uma cauda semelhante à de um cometa é visível durante alguns dias, quando o asteroide passa mais perto do Sol durante a sua órbita.

No entanto, as caudas dos cometas são normalmente formadas pela vaporização de gelo e dióxido de carbono, o que não pode explicar esta cauda. A cauda deveria ser visível já à distância de Júpiter em torno do Sol.

Quando a camada superficial de um asteroide se quebra, o cascalho e a

poeira desprendidos continuam a viajar na mesma órbita e dão origem a

um enxame de estrelas cadentes quando encontram a Terra.

Faetonte provoca a chuva de meteoros das Geminídeas,

que aparece nos céus todos os anos em meados de dezembro. Pelo menos de

acordo com a hipótese prevalente, porque é nessa altura que a Terra

atravessa o percurso do asteroide.

Até à data, as teorias sobre o que acontece à superfície de Faetonte,

perto do Sol, permaneceram puramente hipotéticas. O que é que sai do

asteroide? Como?

A resposta a este enigma foi encontrada através da compreensão da composição de Faetonte.

Um grupo raro de meteoritos

Num estudo recentemente publicado

na revista Nature Astronomy por investigadores da Universidade de

Helsínquia, o espetro infravermelho de Faetonte, anteriormente medido

pelo telescópio espacial Spitzer da NASA, foi reanalisado e comparado

com espetros infravermelhos de meteoritos medidos em laboratório.

Os investigadores descobriram que o espetro de Faetonte corresponde exatamente a um certo tipo de meteorito, o chamado condrito carbonáceo CY. Trata-se de um tipo de meteorito muito raro, do qual apenas se conhecem seis exemplares.

Os asteroides também podem ser estudados através da recolha de

amostras no espaço, mas os meteoritos podem ser estudados sem missões

espaciais dispendiosas. Os asteroides Ryugu e Bennu, alvos de recentes missões de recolha de amostras da JAXA e da NASA, pertencem aos meteoritos CI e CM.

Os três tipos de meteoritos têm origem no nascimento do Sistema Solar e assemelham-se parcialmente uns aos outros, mas apenas o grupo CY mostra sinais de secagem e decomposição térmica devido a um aquecimento recente.

Todos os três grupos mostram sinais de uma mudança

que ocorreu durante a evolução inicial do Sistema Solar, onde a água se

combina com outras moléculas para formar minerais de filossilicatos e

carbonato.

No entanto, os meteoritos do tipo CY diferem dos outros devido ao seu

elevado teor de sulfureto de ferro, o que sugere a sua própria origem.

Espetros dos condritos carbonáceos CY

A análise do espetro infravermelho de Faetonte mostrou que o asteroide era composto de pelo menos olivina, carbonatos, sulfuretos de ferro e minerais de óxido. Todos estes minerais apoiam a ligação aos meteoritos CY, especialmente o sulfureto de ferro.

Os carbonatos sugerem alterações no conteúdo de água

que se enquadram na composição primitiva, enquanto a olivina é um

produto da decomposição térmica de filossilicatos a temperaturas

extremas.

Na investigação, foi possível mostrar com modelação térmica quais as

temperaturas que prevalecem na superfície do asteroide e quando certos

minerais se decompõem e libertam gases.

Quando Faetonte passa perto do Sol, a temperatura da sua superfície aumenta para cerca de 800°C. O grupo de meteoritos CY encaixa-se bem nesta situação.

A temperaturas semelhantes, os carbonatos produzem dióxido de carbono, os filossilicatos libertam vapor de água e os sulfuretos o gás enxofre.

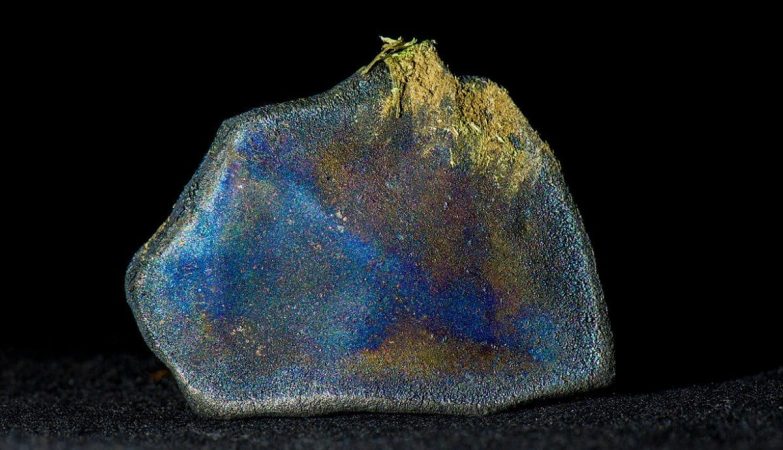

O

investigador pós-doutoramento Eric MacLennan segura nas mãos um tipo muito

raro de meteorito, o chamado condrito carbonáceo CY. Só se conhecem

seis exemplares do mesmo tipo. A amostra foi emprestada pelo Museu de

História Natural de Londres

De acordo com o estudo, todos os minerais identificados em Faetonte

parecem corresponder aos minerais dos meteoritos do tipo CY. As únicas

exceções foram os óxidos portlandita e brucita, que não foram detetados

nos meteoritos.

No entanto, estes minerais podem formar-se quando os carbonatos são aquecidos e destruídos na presença de vapor de água.

Cauda e chuva de meteoros têm uma explicação

A composição e a temperatura do asteroide explicam a formação de gás

perto do Sol, mas será que também explicam a poeira e o cascalho que

formam os meteoros das Geminídeas? Será que o asteroide tinha pressão suficiente para levantar poeira e rocha da sua superfície?

Os investigadores utilizaram dados experimentais de outros estudos em

conjunto com os seus modelos térmicos e, com base neles, estimaram que,

quando o asteroide passa mais perto do Sol, é libertado gás da estrutura mineral do asteroide, o que pode provocar a desagregação da rocha.

Além disso, a pressão produzida pelo dióxido de carbono e pelo vapor de água é suficientemente elevada para levantar pequenas partículas de poeira da superfície do asteroide.

“A emissão de sódio pode explicar a fraca cauda que observamos perto

do Sol, e a decomposição térmica pode explicar a forma como a poeira e o

cascalho são libertados de Faetonte”, diz o autor principal do estudo, o

investigador de pós-doutoramento Eric MacLennan, da Universidade de Helsínquia.

“Foi fantástico ver como cada um dos minerais descobertos parecia

encaixar-se e também explicar o comportamento do asteroide”, resume o

professor associado Mikael Granvik, da Universidade de Helsínquia.

in ZAP