Artigo da revista "Science"

Há um bocadinho de Neandertal dentro de nós

Svante Pääbo, investigador do Instituto Max Planck de Antropologia Evolutiva de Leipzig, na Alemanha

O debate durou anos: o homem moderno (nós) e o Homem de Neandertal, hoje extinto, ter-se-iam cruzado e procriado juntos – ou não? Hoje a questão foi definitivamente arrumada pela genética, com a publicação na "Science" do primeiro rascunho do genoma dos Neandertais. A resposta? Sim! A criança do Lapedo teve de facto Neandertais entre os seus antepassados.

Há meses que nos diziam que a primeira sequenciação do genoma do Homem de Neandertal estava quase pronta. Já está. E proporcionou uma primeira grande surpresa aos próprios autores do trabalho (que, como muitos outros especialistas, não acreditavam nesta possibilidade), ao confirmar que os humanos modernos acasalaram e procriaram com Neandertais. Simplesmente, porque descobriram bocadinhos de sequências genéticas de Neandertal no nosso ADN.

A equipa internacional liderada por Svante Pääbo, do Instituto Max Planck de Antropologia Evolutiva de Leipzig, na Alemanha, demorou quatro anos a ler os genes desse ser humano, extinto há cerca de 30 mil anos – uma proeza técnica que, segundo os autores, vai ao mesmo tempo permitir perceber o que é que nos distingue deles do ponto de vista evolutivo.

“Há seis ou sete anos, eu pensava que a sequenciação da totalidade de um genoma antigo era algo que não iria acontecer durante a minha vida”, disse ontem Pääbo no início de uma conferência de imprensa telefónica convocada pela revista Science. O grande problema, explicou, é que “mais de 90 por cento do ADN encontrado nos fósseis provinha de bactérias ou de fungos” – ou seja, pertencia aos microrganismos que tinham contaminado os ossos após a morte dos indivíduos em questão. Para mais, os fragmentos de ADN obtidos eram extremamente curtos e tinham sofrido alterações químicas. Isto sem esquecer que a sua mera manipulação corria o risco de introduzir uma contaminação adicional, com o próprio ADN dos cientistas – o que é absolutamente indesejável quando se trata justamente de determinar se há genes de Neandertal em nós ou genes nossos neles... Uma grande parte do trabalho e das técnicas desenvolvidas tinha portanto como objectivo garantir a autenticidade da proveniência do ADN em estudo.

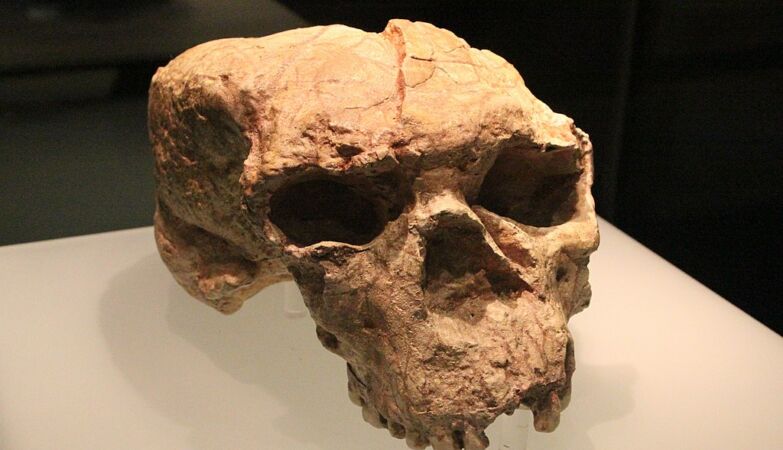

Os cientistas extraíram o ADN principalmente de três fragmentos de osso fossilizado de três mulheres Neandertais, que tinham sido encontrados numa gruta na Croácia entre o fim da década de 1970 e o início da de 1980. Dois desses ossos foram datados com precisão e têm respectivamente 38 mil e 44 mil anos. A partir daí, conseguiu-se reconstituir, nesta primeira fase, cerca de 60 por cento da totalidade dos três mil milhões de pares de bases (ou “letras”) do ADN dos Neandertais.

Aconteceu no Médio Oriente

Os cientistas também sequenciaram cinco genomas de humanos actuais, de origem europeia, asiática e africana, para fins de comparação com o genoma fóssil – e compararam ainda esse genoma com o do chimpanzé. E descobriram que os Neandertais são, do ponto de vista genético, ligeiramente mais próximos dos humanos modernos fora de África do que dos africanos actuais. A explicação que dão para isto é que, pouco depois de terem saído de África à conquista do mundo, há uns 80 mil anos, provavelmente algures no Médio Oriente (antes de chegarem à Europa), os primeiros homens modernos cruzaram-se com os Neandertais e produziram descendência.

Isso não significa que não tenha havido, mais tarde, novos encontros e novos cruzamentos, nomeadamente na Europa. Mas o “fluxo genético” agora detectado – sempre dos Neandertais para os humanos actuais e não em sentido oposto – aponta para um contacto mais precoce, logo à saída de África. A ausência de provas não significa que não tenha havido contactos ulteriores, mas simplesmente que não foi possível detectar sinais genéticos desses contactos, argumentam os cientistas.

Seja como for, os seres humanos actuais, da Austrália à Europa, passando pela Ásia (mas não por África), herdaram, naquela altura, bocadinhos de sequências genéticas de Neandertal que continuam, ainda hoje, espalhadas pelo nosso ADN. Os cientistas estimam que entre um e quatro por cento do genoma dos humanos actuais provenha dos Neandertais. Num comunicado, referem mesmo que o genoma do célebre “caça-genes” norte-americano Craig Venter, recentemente publicado, contém segmentos que são mais próximos do genoma de Neandertal do que do genoma “de referência” humano, que inclui uma mistura de ADN de origem europeia e africana! “Um a quatro por cento do meu genoma é Neandertal”, salientou Pääbo na conferência de ontem. “Eles não se extinguiram totalmente, continuam a viver em nós.” Contudo, as sequências genéticas identificadas como provenientes dos Neandertais estão distribuídas ao acaso pela molécula de ADN e não correspondem a nenhum traço identificável que alguns de nós poderíamos ter em comum com eles.

Para Pääbo, “o mais fascinante” disto tudo é, porém, a possibilidade de utilizar este genoma fóssil para procurar provas da selecção “positiva” de traços genéticos, ou seja, de características genéticas que se fixaram ulteriormente nos humanos modernos porque apresentavam vantagens do ponto de vista evolutivo em termos de sobrevivência da espécie – e que nos tornam únicos e diferentes dos Neandertais. A equipa já identificou várias regiões do genoma onde isto poderá ter acontecido, que têm a ver com o desenvolvimento mental e cognitivo (há três genes que, quando mutados, estão implicados na trissomia 21, na esquizofrenia e no autismo), bem como regiões relacionadas com o metabolismo energético, com o desenvolvimento do crânio, da clavícula e da caixa torácica.

Pertencemos à mesma espécie?

Para Pääbo, esta pergunta não faz sentido. “É um debate estéril”, frisou. “Nunca me pronunciei sobre isto e prefiro deixar essas lutas a outros. O que interessa é que mostrámos que o cruzamento reprodutivo era biologicamente possível entre os Neandertais e nós. Eu diria que eram diferente dos humanos – mas não assim tão diferentes como isso.”

“Há mais de dez anos que as provas arqueológicas e paleontológicas de hibridação cultural e biológica entre Neandertais e homens modernos se vêm acumulando”, disse João Zilhão, arqueólogo português da Universidade de Bristol, em conversa telefónica com o PÚBLICO. Juntamente com o seu colega Erik Trinkaus, da Universidade de Washington, Zilhão descobriu em 1998, no Vale do Lapedo, perto de Leiria, o esqueleto mais completo até à data de uma criança da nossa espécie que viveu no Paleolítico Superior (há cerca de 25 mil anos). O fóssil, afirmam desde então estes cientistas, apresenta uma mistura de traços modernos e de Neandertal.

Só que muitos especialistas discordavam desta interpretação – o que, para Zilhão, deixa de ser possível a partir de hoje. “Andámos a dizer isso há dez anos e têm-nos atirado à cara com os dados genéticos”, disse-nos hoje o investigador. E mostrou-se satisfeito com os novos resultados: “Era a última objecção contra o nosso modelo e isso é óptimo. Há que virar a página, o problema está resolvido.”

Mas então somos ou não da mesma espécie? “A dicotomia homem moderno/Neandertal é falsa”, responde-nos Zilhão. “É uma classificação vitoriana, do século XIX.” O Neandertal foi o primeiro homem fóssil a ser descoberto, um ser a meio caminho entre os macacos e o homem, “e isso encaixava no paradigma da evolução [das espécies]”. Para Zilhão, esta concepção tem criado uma resistência cultural subconsciente. “Como é que um fulano tão feio pode ser igual a nós?”, ironiza. “Do ponto de vista biológico, o que é importante é que, em termos reprodutivos, o homem moderno e o homem de Neandertal funcionam como uma única comunidade. Podiam acasalar. Isso é que conta.”

É provável, entretanto, que o crescente número de pessoas que recorrem a empresas que analisam o seu genoma venham a saber em breve se são portadoras de sequências genéticas vindas dos Neandertais. Até porque o genoma fóssil já foi colocado pelos autores na Internet, numa base de dados genética de acesso livre. Interrogado pelo PÚBLICO a este propósito durante a conferência de imprensa de ontem, Pääbo riu-se: “Tenho a certeza de que algumas dessas empresas vão oferecer isso aos seus clientes.”