The military tribunal considered guilt and sentencing on June 29 and 30. Surratt's guilt was the second-to-last considered, because her case presented problems of evidence and witness reliability. Sentence was handed down June 30. The military tribunal found Mary Surratt guilty on all charges but two. A death sentence required six of the nine votes of the judges. Surratt was sentenced to death, and the sentence announced publicly on July 5. When Powell learned of his sentence, he declared that Mary Surratt was completely innocent of all charges. The night before the execution, Surratt's priests and Anna Surratt both visited Powell, and elicited from him a strong statement declaring Mrs. Surratt innocent. Although this was delivered to Captain Christian Rath, who was overseeing the execution, Powell's statement had no effect on anyone with authority to prevent Surratt's death. But George Atzerodt bitterly condemned her, implicating her even further in the conspiracy. Powell's was the only statement by any conspirator exonerating Surratt.

Five of the nine judges signed a letter asking President Andrew Johnson to give Surratt clemency and commute her sentence to life in prison, given her age and gender. Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt did not deliver the recommendation to President Johnson until July 5, two days before Surratt and the others were to hang. Johnson signed the order for execution, but did not sign the order for clemency. Johnson later said he never saw the clemency request; Holt said he showed it to Johnson, who refused to sign it. Johnson, according to Holt, said in signing the death warrant that she had "kept the nest that hatched the egg".

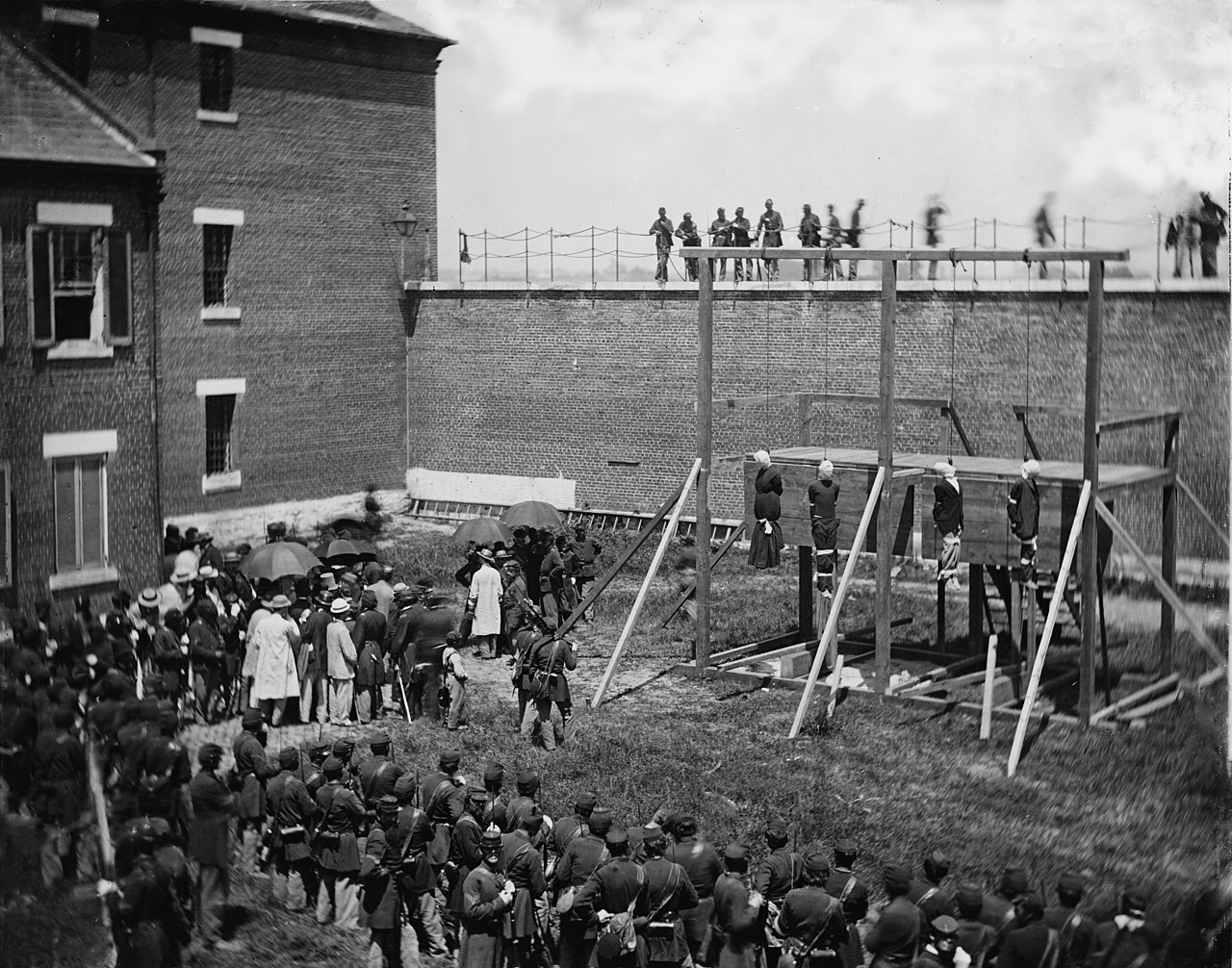

Construction of the

gallows for the hanging of the conspirators condemned to death, among them Mary Surratt, began immediately on July 5 after the execution order was signed. It was constructed in the south part of the Arsenal courtyard, was 12 feet (3.7 m) high and about 20 square feet (1.9 m

2) in size. Captain Christian Rath, who oversaw the preparations for the executions, made the nooses. Tired of making nooses and thinking Surratt would not hang, he made Surratt's

noose the night before the execution with five loops rather than the regulation seven. He tested the nooses that night by tying them to a tree limb and a bag of

buckshot, then tossing the bag to the ground (the ropes held). Civilian workers did not want to dig the graves out of superstitious fear, so Rath asked for volunteers among the soldiers at the Arsenal and received more help than he needed.

At noon on July 6, Surratt was informed she would be hanged the next day. She wept profusely. She was joined by two Catholic priests (Jacob Walter and B.F. Wiget) and her daughter Anna. Father Jacob remained with her almost until her death. Her menstrual problems had worsened, and she was in such pain and suffered from such severe cramps that the prison doctor gave her wine and medication. She repeatedly asserted her innocence. She spent the night on her mattress, weeping and moaning (in pain and grief), ministered to by the priests. Anna left her mother's side at 8 A.M. on July 7, and went to the White House to beg for her mother's life one last time. Her entreaty rejected, she returned to the prison and her mother's cell at about 11 A.M. The soldiers began testing the gallows about 11:25 A.M.; the sound of the tests unnerved all the prisoners. Shortly before noon, Mary Surratt was taken from her cell and then allowed to sit in a chair near the entrance to the courtyard. The heat in the city that day was oppressive. By noon, it had already reached

92.3 °F (33.5 °C). The guards ordered all visitors to leave at 12:30 P.M. When she was forced to part from her mother, Anna's hysterical screams of grief could be heard throughout the prison.

Clampitt and Aiken had not finished trying to save their client, however. On the morning of July 7, they asked a District of Columbia court for a

writ of habeas corpus, arguing that the military tribunal had no jurisdiction over their client. The court issued the writ at 3 A.M., and it was served on General

Winfield Scott Hancock. Hancock was ordered to produce Surratt by 10 A.M. General Hancock sent an aide to General

John F. Hartranft, who commanded the Old Capitol Prison, ordering him not to admit any United States marshal (as this would prevent the marshal from serving a similar writ on Hartranft). President Johnson was informed that the court had issued the writ, and promptly cancelled it at 11:30 A.M. under the authority granted to him by the

Habeas Corpus Suspension Act of 1863. General Hancock and

United States Attorney General James Speed personally appeared in court and informed the judge of the cancellation of the writ.

On July 7, 1865, at 1:15 P.M., a procession led by General Hartranft escorted the four condemned prisoners through the courtyard and up the steps to the gallows. Each prisoner's ankles and wrists were bound by manacles. Mary Surratt led the way, wearing a black

bombazine dress, black

bonnet, and black veil. More than 1,000 people - including government officials, members of the U.S. armed forces, friends and family of the accused, official witnesses, and reporters - watched. General Hancock limited attendance to those who had a ticket, and only those who had a good reason to be present were given a ticket. (Most of those present were military officers and soldiers, as fewer than 200 tickets had been printed.)

Alexander Gardner, who had photographed the body of Booth and taken portraits of several of the male conspirators while they were imprisoned aboard naval ships, photographed the execution for the government. Hartranft read the order for their execution. Surratt, either weak from her illness or swooning in fear (perhaps both), had to be supported by two soldiers and her priests. The condemned were seated in chairs, Surratt almost collapsing into hers. She was seated to the right of the others, the traditional "seat of honor" in an execution. White cloth was used to bind their arms to their sides, and their ankles and thighs together. The cloths around Surratt's legs were tied around her dress below the knees. Each person was ministered to by a member of the clergy. From the scaffold, Powell said, "Mrs. Surratt is innocent. She doesn't deserve to die with the rest of us". Fathers Jacob and Wiget prayed over Mary Surratt, and held a crucifix to her lips. About 16 minutes elapsed from the time the prisoners entered the courtyard until they were ready for execution.

A white bag was placed over the head of each prisoner after the noose was put in place. Surratt's bonnet was removed, and the noose put around her neck by a

Secret Service officer. She complained that the bindings about her arms hurt, and the officer preparing said, "Well, it won't hurt long." Finally, the prisoners were asked to stand and move forward a few feet to the nooses. The chairs were removed. Mary Surratt's last words, spoken to a guard as he moved her forward to the drop, were "Please don't let me fall."

Surratt and the others stood on the drop for about 10 seconds, and then Captain Rath clapped his hands. Four soldiers of Company F of the 14th Veteran Reserves knocked out the supports holding the drops in place, and the condemned fell. Surratt, who had moved forward enough to barely step onto the drop, lurched forward and slid partway down the drop - her body snapping tight at the end of the rope, swinging back and forth. Surratt's death appeared to be the easiest. Atzerodt's stomach heaved once and his legs quivered, and then he was still. Herold and Powell struggled for nearly five minutes, strangling to death.