History and significance

The Burgess Shale was discovered by palaeontologist Charles Walcott

on 30 August 1909, towards the end of the season's fieldwork. He

returned in 1910 with his sons, daughter, and wife, establishing a

quarry on the flanks of Fossil Ridge. The significance of soft-bodied

preservation, and the range of organisms he recognised as new to

science, led him to return to the quarry almost every year until 1924.

At that point, aged 74, he had amassed over 65,000 specimens. Describing

the fossils was a vast task, pursued by Walcott until his death in

1927. Walcott, led by scientific opinion at the time, attempted to

categorise all fossils into living taxa, and as a result, the fossils

were regarded as little more than curiosities at the time. It was not

until 1962 that a first-hand reinvestigation of the fossils was

attempted, by Alberto Simonetta. This led scientists to recognise that

Walcott had barely scratched the surface of information available in

the Burgess Shale, and also made it clear that the organisms did not

fit comfortably into modern groups.

Excavations were resumed at the Walcott Quarry by the Geological Survey of Canada under the persuasion of trilobite expert Harry Blackmore Whittington,

and a new quarry, the Raymond, was established about 20 metres higher

up Fossil Ridge. Whittington, with the help of research students Derek Briggs and Simon Conway Morris of the University of Cambridge,

began a thorough reassessment of the Burgess Shale, and revealed that

the fauna represented were much more diverse and unusual than Walcott

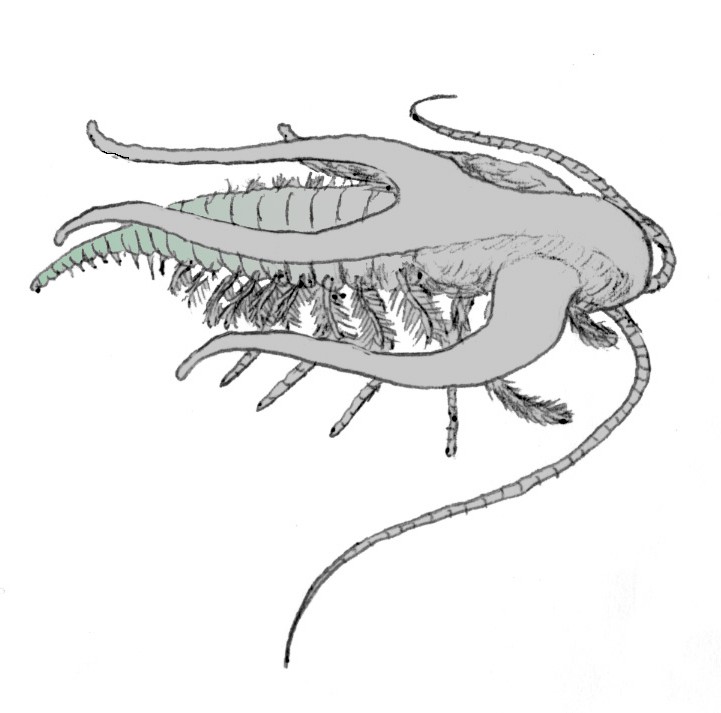

had recognized. Indeed, many of the animals present had bizarre anatomical features and only the slightest resemblance to other known animals. Examples include Opabinia, with five eyes and a snout like a vacuum cleaner hose and Hallucigenia, which was originally reconstructed upside down, walking on bilaterally symmetrical spines.

With Parks Canada and UNESCO

recognising the significance of the Burgess Shale, collecting fossils

became politically more difficult from the mid-1970s. Collections

continued to be made by the Royal Ontario Museum. The curator of invertebrate palaeontology, Desmond Collins, identified a number of additional outcrops, stratigraphically

both higher and lower than the original Walcott quarry. These

localities continue to yield new organisms faster than they can be

studied.

Stephen Jay Gould's book Wonderful Life,

published in 1989, brought the Burgess Shale fossils to the public's

attention. Gould suggests that the extraordinary diversity of the

fossils indicates that life forms at the time were much more disparate

in body form than those that survive today, and that many of the unique

lineages were evolutionary experiments that became extinct. Gould's

interpretation of the diversity of Cambrian fauna relied heavily on Simon Conway Morris's

reinterpretation of Charles Walcott's original publications. However,

Conway Morris strongly disagreed with Gould's conclusions, arguing that

almost all the Cambrian fauna could be classified into modern day phyla.

The Burgess Shale has attracted the interest of paleoclimatologists who want to study and predict long-term future changes in Earth's climate. According to Peter Ward and Donald Brownlee in the 2003 book The Life and Death of Planet Earth, climatologists study the fossil records in the Burgess Shale to understand the climate of the Cambrian explosion,

and use it to predict what Earth's climate would look like 500 million

years in the future when a warming and expanding Sun combined with

declining CO2 and oxygen levels eventually heat the Earth toward temperatures not seen since the Archean

Eon 3 billion years ago, before the first plants and animals appeared,

and therefore understand how and when the last living things will die

out.

After the Burgess Shale site was registered as a World Heritage Site in 1980, it was included in the Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks WHS designation in 1984.

In February 2014, the discovery was announced of another Burgess Shale outcrop in Kootenay National Park to the south. In just 15 days of field collecting in 2013, 50 animal species were unearthed at the new site.