quinta-feira, dezembro 18, 2025

Biko...

Postado por Pedro Luna às 07:09 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, assassinato, Biko, Black is Beautiful, direitos humanos, música, Peter Gabriel, Steve Biko

Steve Biko nasceu há 79 anos...

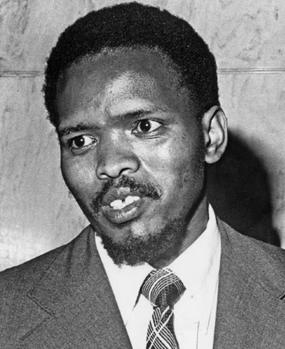

Stephen Bantu Biko (Ginsberg Township, 18 de dezembro de 1946 - Pretoria, 12 de setembro de 1977) foi um ativista anti-apartheid da África do Sul na década de 60 e 70.

Postado por Fernando Martins às 00:07 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, assassinato, Biko, Black is Beautiful, direitos humanos, Steve Biko

sexta-feira, setembro 12, 2025

Biko...

Biko - Peter Gabriel

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo, kophalal'igazi!

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo, kophalal'igazi!

Bakhala uVorster!

Bakhala uVorster!

Ngomhla sibuyayo, kophalal'igazi!

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo, kophalal'igazi!

September '77

Port Elizabeth weather fine

It was business as usual

In police room 619

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Yihla moja, yihla moja

The man is dead

The man is dead

When I try and sleep at night

I can only dream in red

The outside world is black and white

With only one colour dead

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Yihla moja, yihla moja

The man is dead

The man is dead

You can blow out a candle

But you can't blow out a fire

Once the flames begin to catch

The wind will blow it higher

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Yihla moja, yihla moja

The man is dead

The man is dead

Are watching now

Watching now

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Postado por Pedro Luna às 04:08 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, Biko, direitos humanos, música, Peter Gabriel, Steve Biko, tortura

O apartheid da África do Sul assassinou Steve Biko há 48 anos...

On 11 September 1977, police loaded him in the back of a Land Rover, naked and restrained in manacles, and began the 1,100 kilometres (680 mi) drive to Pretoria to take him to a prison with hospital facilities. He was nearly dead owing to the previous injuries. He died shortly after arrival at the Pretoria prison, on 12 September. The police claimed his death was the result of an extended hunger strike, but an autopsy revealed multiple bruises and abrasions and that he ultimately succumbed to a brain hemorrhage from the massive injuries to the head, which many saw as strong evidence that he had been brutally clubbed by his captors. Then Donald Woods, a journalist, editor and close friend of Biko's, along with Helen Zille, later leader of the Democratic Alliance political party, exposed the truth behind Biko's death.

Because of his high profile, news of Biko's death spread quickly, publicizing the repressive nature of the apartheid government. His funeral was attended by over 10,000 people, including numerous ambassadors and other diplomats from the United States and Western Europe. Donald Woods, who photographed his injuries in the morgue as proof of police abuse, was later forced to flee South Africa for England. Woods later campaigned against apartheid and further publicised Biko's life and death, writing many newspaper articles and authoring the book, Biko, which was later turned into the film Cry Freedom. Speaking at a National Party conference following the news of Biko's death then–minister of police, Jimmy Kruger said, "I am not glad and I am not sorry about Mr. Biko. It leaves me cold (Dit laat my koud). I can say nothing to you ... Any person who dies ... I shall also be sorry if I die."

After a 15-day inquest in 1978, a magistrate judge found there was not enough evidence to charge the officers with murder because there were no eyewitnesses. On 2 February 1978, based on the evidence given at the inquest, the attorney general of the Eastern Cape stated he would not prosecute. On 28 July 1979, the attorney for Biko's family announced that the South African government would pay them $78,000 in compensation for Biko's death.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was created following the end of minority rule and the apartheid system, reported that five former members of the South African security forces who had admitted to killing Biko were applying for amnesty. Their application was rejected in 1999.

On 7 October 2003, the South African justice ministry announced that the five policemen accused of killing Biko would not be prosecuted because the time limit for prosecution had elapsed and because of insufficient evidence.

A year after his death, some of his writings were collected and released under the title I Write What I Like.

Postado por Fernando Martins às 00:48 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, Biko, direitos humanos, música, Steve Biko, tortura

quarta-feira, dezembro 18, 2024

Steve Biko nasceu há 78 anos...

Stephen Bantu Biko (Ginsberg Township, 18 de dezembro de 1946 - Pretoria, 12 de setembro de 1977) foi um ativista anti-apartheid da África do Sul na década de 60 e 70.

Postado por Fernando Martins às 07:08 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, assassinato, Biko, Black is Beautiful, direitos humanos, música, Peter Gabriel, Steve Biko

quinta-feira, setembro 12, 2024

Biko...

Biko - Peter Gabriel

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo, kophalal'igazi!

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo, kophalal'igazi!

Bakhala uVorster!

Bakhala uVorster!

Ngomhla sibuyayo, kophalal'igazi!

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo, kophalal'igazi!

September '77

Port Elizabeth weather fine

It was business as usual

In police room 619

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Yihla moja, yihla moja

The man is dead

The man is dead

When I try and sleep at night

I can only dream in red

The outside world is black and white

With only one colour dead

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Yihla moja, yihla moja

The man is dead

The man is dead

You can blow out a candle

But you can't blow out a fire

Once the flames begin to catch

The wind will blow it higher

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Yihla moja, yihla moja

The man is dead

The man is dead

Are watching now

Watching now

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Postado por Pedro Luna às 04:07 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, Biko, direitos humanos, música, Peter Gabriel, Steve Biko, tortura

Steve Biko foi assassinado há 47 anos...

On 11 September 1977, police loaded him in the back of a Land Rover, naked and restrained in manacles, and began the 1,100 kilometres (680 mi) drive to Pretoria to take him to a prison with hospital facilities. He was nearly dead owing to the previous injuries. He died shortly after arrival at the Pretoria prison, on 12 September. The police claimed his death was the result of an extended hunger strike, but an autopsy revealed multiple bruises and abrasions and that he ultimately succumbed to a brain hemorrhage from the massive injuries to the head, which many saw as strong evidence that he had been brutally clubbed by his captors. Then Donald Woods, a journalist, editor and close friend of Biko's, along with Helen Zille, later leader of the Democratic Alliance political party, exposed the truth behind Biko's death.

Because of his high profile, news of Biko's death spread quickly, publicizing the repressive nature of the apartheid government. His funeral was attended by over 10,000 people, including numerous ambassadors and other diplomats from the United States and Western Europe. Donald Woods, who photographed his injuries in the morgue as proof of police abuse, was later forced to flee South Africa for England. Woods later campaigned against apartheid and further publicised Biko's life and death, writing many newspaper articles and authoring the book, Biko, which was later turned into the film Cry Freedom. Speaking at a National Party conference following the news of Biko's death then–minister of police, Jimmy Kruger said, "I am not glad and I am not sorry about Mr. Biko. It leaves me cold (Dit laat my koud). I can say nothing to you ... Any person who dies ... I shall also be sorry if I die."

After a 15-day inquest in 1978, a magistrate judge found there was not enough evidence to charge the officers with murder because there were no eyewitnesses. On 2 February 1978, based on the evidence given at the inquest, the attorney general of the Eastern Cape stated he would not prosecute. On 28 July 1979, the attorney for Biko's family announced that the South African government would pay them $78,000 in compensation for Biko's death.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was created following the end of minority rule and the apartheid system, reported that five former members of the South African security forces who had admitted to killing Biko were applying for amnesty. Their application was rejected in 1999.

On 7 October 2003, the South African justice ministry announced that the five policemen accused of killing Biko would not be prosecuted because the time limit for prosecution had elapsed and because of insufficient evidence.

A year after his death, some of his writings were collected and released under the title I Write What I Like.

Postado por Fernando Martins às 00:47 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, Biko, direitos humanos, música, Steve Biko, tortura

segunda-feira, dezembro 18, 2023

Steve Biko nasceu há 77 anos...

Stephen Bantu Biko (Ginsberg Township, 18 de dezembro de 1946 - Pretoria, 12 de setembro de 1977) foi um ativista anti-apartheid da África do Sul na década de 60 e 70.

Postado por Fernando Martins às 07:07 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, assassinato, Biko, Black is Beautiful, direitos humanos, música, Peter Gabriel, Steve Biko

terça-feira, setembro 12, 2023

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko...

Biko - Peter Gabriel

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo, kophalal'igazi!

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo, kophalal'igazi!

Bakhala uVorster!

Bakhala uVorster!

Ngomhla sibuyayo, kophalal'igazi!

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo, kophalal'igazi!

September '77

Port Elizabeth weather fine

It was business as usual

In police room 619

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Yihla moja, yihla moja

The man is dead

The man is dead

When I try and sleep at night

I can only dream in red

The outside world is black and white

With only one colour dead

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Yihla moja, yihla moja

The man is dead

The man is dead

You can blow out a candle

But you can't blow out a fire

Once the flames begin to catch

The wind will blow it higher

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Yihla moja, yihla moja

The man is dead

The man is dead

Are watching now

Watching now

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Postado por Pedro Luna às 04:06 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, Biko, direitos humanos, música, Peter Gabriel, Steve Biko, tortura

Steve Biko foi brutalmente assassinado há 46 anos...

On 11 September 1977, police loaded him in the back of a Land Rover, naked and restrained in manacles, and began the 1,100 kilometres (680 mi) drive to Pretoria to take him to a prison with hospital facilities. He was nearly dead owing to the previous injuries. He died shortly after arrival at the Pretoria prison, on 12 September. The police claimed his death was the result of an extended hunger strike, but an autopsy revealed multiple bruises and abrasions and that he ultimately succumbed to a brain hemorrhage from the massive injuries to the head, which many saw as strong evidence that he had been brutally clubbed by his captors. Then Donald Woods, a journalist, editor and close friend of Biko's, along with Helen Zille, later leader of the Democratic Alliance political party, exposed the truth behind Biko's death.

Because of his high profile, news of Biko's death spread quickly, publicizing the repressive nature of the apartheid government. His funeral was attended by over 10,000 people, including numerous ambassadors and other diplomats from the United States and Western Europe. Donald Woods, who photographed his injuries in the morgue as proof of police abuse, was later forced to flee South Africa for England. Woods later campaigned against apartheid and further publicised Biko's life and death, writing many newspaper articles and authoring the book, Biko, which was later turned into the film Cry Freedom. Speaking at a National Party conference following the news of Biko's death then–minister of police, Jimmy Kruger said, "I am not glad and I am not sorry about Mr. Biko. It leaves me cold (Dit laat my koud). I can say nothing to you ... Any person who dies ... I shall also be sorry if I die."

After a 15-day inquest in 1978, a magistrate judge found there was not enough evidence to charge the officers with murder because there were no eyewitnesses. On 2 February 1978, based on the evidence given at the inquest, the attorney general of the Eastern Cape stated he would not prosecute. On 28 July 1979, the attorney for Biko's family announced that the South African government would pay them $78,000 in compensation for Biko's death.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was created following the end of minority rule and the apartheid system, reported that five former members of the South African security forces who had admitted to killing Biko were applying for amnesty. Their application was rejected in 1999.

On 7 October 2003, the South African justice ministry announced that the five policemen accused of killing Biko would not be prosecuted because the time limit for prosecution had elapsed and because of insufficient evidence.

A year after his death, some of his writings were collected and released under the title I Write What I Like.

Postado por Fernando Martins às 00:46 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, Biko, direitos humanos, música, Steve Biko, tortura

domingo, dezembro 18, 2022

Steve Biko nasceu há 76 anos...

Stephen Bantu Biko (Ginsberg Township, 18 de dezembro de 1946 - Pretoria, 12 de setembro de 1977) foi um ativista anti-apartheid da África do Sul na década de 60 e 70.

Postado por Fernando Martins às 07:06 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, assassinato, Biko, Black is Beautiful, direitos humanos, música, Peter Gabriel, Steve Biko

segunda-feira, setembro 12, 2022

Biko...

Postado por Pedro Luna às 04:50 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, Biko, direitos humanos, música, Peter Gabriel, Steve Biko, tortura

Steve Biko foi assassinado há 45 anos...

On 11 September 1977, police loaded him in the back of a Land Rover, naked and restrained in manacles, and began the 1,100 kilometres (680 mi) drive to Pretoria to take him to a prison with hospital facilities. He was nearly dead owing to the previous injuries. He died shortly after arrival at the Pretoria prison, on 12 September. The police claimed his death was the result of an extended hunger strike, but an autopsy revealed multiple bruises and abrasions and that he ultimately succumbed to a brain hemorrhage from the massive injuries to the head, which many saw as strong evidence that he had been brutally clubbed by his captors. Then Donald Woods, a journalist, editor and close friend of Biko's, along with Helen Zille, later leader of the Democratic Alliance political party, exposed the truth behind Biko's death.

Because of his high profile, news of Biko's death spread quickly, publicizing the repressive nature of the apartheid government. His funeral was attended by over 10,000 people, including numerous ambassadors and other diplomats from the United States and Western Europe. Donald Woods, who photographed his injuries in the morgue as proof of police abuse, was later forced to flee South Africa for England. Woods later campaigned against apartheid and further publicised Biko's life and death, writing many newspaper articles and authoring the book, Biko, which was later turned into the film Cry Freedom. Speaking at a National Party conference following the news of Biko's death then–minister of police, Jimmy Kruger said, "I am not glad and I am not sorry about Mr. Biko. It leaves me cold (Dit laat my koud). I can say nothing to you ... Any person who dies ... I shall also be sorry if I die."

After a 15-day inquest in 1978, a magistrate judge found there was not enough evidence to charge the officers with murder because there were no eyewitnesses. On 2 February 1978, based on the evidence given at the inquest, the attorney general of the Eastern Cape stated he would not prosecute. On 28 July 1979, the attorney for Biko's family announced that the South African government would pay them $78,000 in compensation for Biko's death.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was created following the end of minority rule and the apartheid system, reported that five former members of the South African security forces who had admitted to killing Biko were applying for amnesty. Their application was rejected in 1999.

On 7 October 2003, the South African justice ministry announced that the five policemen accused of killing Biko would not be prosecuted because the time limit for prosecution had elapsed and because of insufficient evidence.

A year after his death, some of his writings were collected and released under the title I Write What I Like.

Postado por Fernando Martins às 00:45 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, Biko, direitos humanos, música, Steve Biko, tortura

sábado, dezembro 18, 2021

Steve Biko nasceu há 75 anos...

Stephen Bantu Biko (Ginsberg Township, 18 de dezembro de 1946 - Pretoria, 12 de setembro de 1977) foi um ativista anti-apartheid da África do Sul na década de 60 e 70.

Postado por Fernando Martins às 07:50 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, assassinato, Biko, Black is Beautiful, direitos humanos, música, Peter Gabriel, Steve Biko

domingo, setembro 12, 2021

Steve Biko foi assassinado há 44 anos...

On 11 September 1977, police loaded him in the back of a Land Rover, naked and restrained in manacles, and began the 1,100 kilometres (680 mi) drive to Pretoria to take him to a prison with hospital facilities. He was nearly dead owing to the previous injuries. He died shortly after arrival at the Pretoria prison, on 12 September. The police claimed his death was the result of an extended hunger strike, but an autopsy revealed multiple bruises and abrasions and that he ultimately succumbed to a brain hemorrhage from the massive injuries to the head, which many saw as strong evidence that he had been brutally clubbed by his captors. Then Donald Woods, a journalist, editor and close friend of Biko's, along with Helen Zille, later leader of the Democratic Alliance political party, exposed the truth behind Biko's death.

Because of his high profile, news of Biko's death spread quickly, publicizing the repressive nature of the apartheid government. His funeral was attended by over 10,000 people, including numerous ambassadors and other diplomats from the United States and Western Europe. Donald Woods, who photographed his injuries in the morgue as proof of police abuse, was later forced to flee South Africa for England. Woods later campaigned against apartheid and further publicised Biko's life and death, writing many newspaper articles and authoring the book, Biko, which was later turned into the film Cry Freedom. Speaking at a National Party conference following the news of Biko's death then–minister of police, Jimmy Kruger said, "I am not glad and I am not sorry about Mr. Biko. It leaves me cold (Dit laat my koud). I can say nothing to you ... Any person who dies ... I shall also be sorry if I die."

After a 15-day inquest in 1978, a magistrate judge found there was not enough evidence to charge the officers with murder because there were no eyewitnesses. On 2 February 1978, based on the evidence given at the inquest, the attorney general of the Eastern Cape stated he would not prosecute. On 28 July 1979, the attorney for Biko's family announced that the South African government would pay them $78,000 in compensation for Biko's death.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was created following the end of minority rule and the apartheid system, reported that five former members of the South African security forces who had admitted to killing Biko were applying for amnesty. Their application was rejected in 1999.

On 7 October 2003, the South African justice ministry announced that the five policemen accused of killing Biko would not be prosecuted because the time limit for prosecution had elapsed and because of insufficient evidence.

A year after his death, some of his writings were collected and released under the title I Write What I Like.

Postado por Fernando Martins às 00:44 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, Biko, direitos humanos, música, Peter Gabriel, Simple Minds, Steve Biko, tortura

sexta-feira, dezembro 18, 2020

Steve Biko nasceu há 74 anos

Stephen Bantu Biko (Ginsberg Township, 18 de dezembro de 1946 - Pretoria, 12 de setembro de 1977) foi um ativista anti-apartheid da África do Sul na década de 60 e 70.

Postado por Fernando Martins às 07:40 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, assassinato, Biko, Black is Beautiful, direitos humanos, música, Peter Gabriel, Steve Biko

sábado, setembro 12, 2020

Steve Biko foi brutalmente assassinado há 43 anos

On 11 September 1977, police loaded him in the back of a Land Rover, naked and restrained in manacles, and began the 1,100 kilometres (680 mi) drive to Pretoria to take him to a prison with hospital facilities. He was nearly dead owing to the previous injuries. He died shortly after arrival at the Pretoria prison, on 12 September. The police claimed his death was the result of an extended hunger strike, but an autopsy revealed multiple bruises and abrasions and that he ultimately succumbed to a brain hemorrhage from the massive injuries to the head, which many saw as strong evidence that he had been brutally clubbed by his captors. Then Donald Woods, a journalist, editor and close friend of Biko's, along with Helen Zille, later leader of the Democratic Alliance political party, exposed the truth behind Biko's death.

Because of his high profile, news of Biko's death spread quickly, publicizing the repressive nature of the apartheid government. His funeral was attended by over 10,000 people, including numerous ambassadors and other diplomats from the United States and Western Europe. Donald Woods, who photographed his injuries in the morgue as proof of police abuse, was later forced to flee South Africa for England. Woods later campaigned against apartheid and further publicised Biko's life and death, writing many newspaper articles and authoring the book, Biko, which was later turned into the film Cry Freedom. Speaking at a National Party conference following the news of Biko's death then–minister of police, Jimmy Kruger said, "I am not glad and I am not sorry about Mr. Biko. It leaves me cold (Dit laat my koud). I can say nothing to you ... Any person who dies ... I shall also be sorry if I die."

After a 15-day inquest in 1978, a magistrate judge found there was not enough evidence to charge the officers with murder because there were no eyewitnesses. On 2 February 1978, based on the evidence given at the inquest, the attorney general of the Eastern Cape stated he would not prosecute. On 28 July 1979, the attorney for Biko's family announced that the South African government would pay them $78,000 in compensation for Biko's death.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was created following the end of minority rule and the apartheid system, reported that five former members of the South African security forces who had admitted to killing Biko were applying for amnesty. Their application was rejected in 1999.

On 7 October 2003, the South African justice ministry announced that the five policemen accused of killing Biko would not be prosecuted because the time limit for prosecution had elapsed and because of insufficient evidence.

A year after his death, some of his writings were collected and released under the title I Write What I Like.

Postado por Fernando Martins às 04:30 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, Biko, direitos humanos, música, Peter Gabriel, Steve Biko, tortura

quinta-feira, setembro 12, 2019

Biko foi assassinado há 42 anos...

Postado por Fernando Martins às 00:42 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, assassinato, Biko, Steve Biko

terça-feira, setembro 12, 2017

Steve Biko foi assassinado há quarenta anos

Postado por Fernando Martins às 00:40 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, assassinato, Biko, Black is Beautiful, direitos humanos, música, Peter Gabriel, Simple Minds, Steve Biko

sexta-feira, dezembro 18, 2015

Steve Biko nasceu há 69 anos

Postado por Fernando Martins às 06:09 0 comentários

Marcadores: África do Sul, apartheid, assassinato, Biko, Black is Beautiful, direitos humanos, música, Peter Gabriel, Steve Biko, Youssou N'Dour