The 1811–1812 New Madrid earthquakes were an intense intraplate earthquake series beginning with an initial earthquake of moment magnitude (7,5 -7,9) on December 16, 1811 followed by a moment magnitude 7,4 aftershock on the same day. They remain the most powerful earthquakes to hit the contiguous United States east of the Rocky Mountains in recorded history. They, as well as the seismic zone of their occurrence, were named for the Mississippi River town of New Madrid, then part of the Louisiana Territory, now within Missouri.

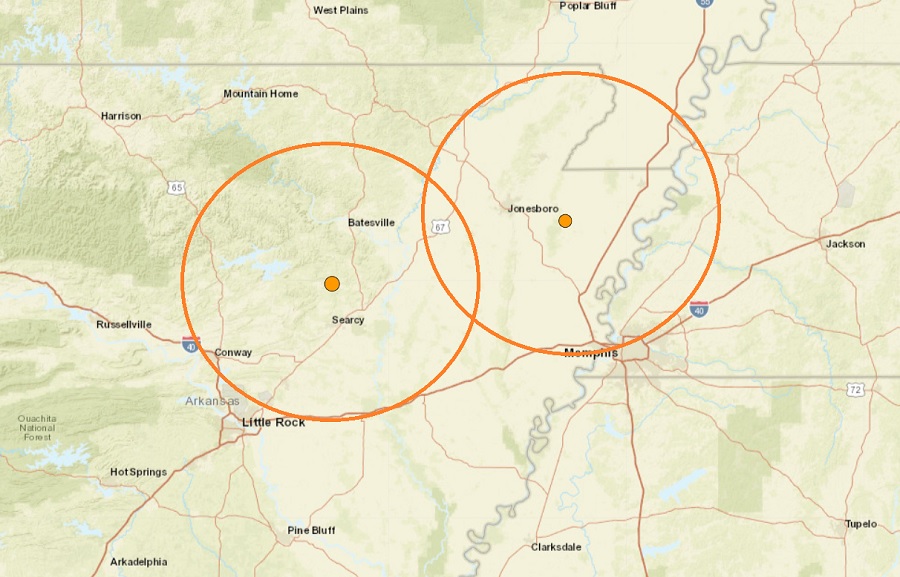

- December 16, 1811, 08.15 UTC (2:15 a.m.); (M 7,5 -7,9) epicenter in northeast Arkansas. It caused only slight damage to manmade structures, mainly because of the sparse population in the epicentral area. The future location of Memphis, Tennessee, experienced level IX shaking on the Mercalli intensity scale. A seismic seiche propagated upriver, and Little Prairie (a village that was on the site of the former Fort San Fernando, near the site of present-day Caruthersville, Missouri) was heavily damaged by soil liquefaction.

- December 16, 1811 (aftershock), 14.15 UTC (8:15 a.m.); (M 7,4) epicenter in northeast Arkansas. This shock followed the first earthquake by five hours and was similar in intensity.

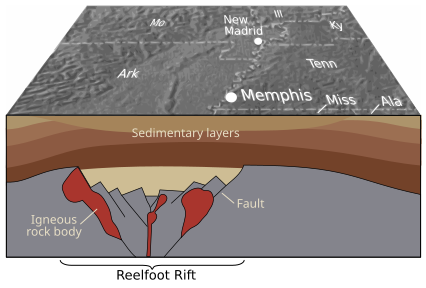

- January 23, 1812, 15.00 UTC (9:00 a.m.); (M 7,3 -7,6) epicenter in the Missouri Bootheel. The meizoseismal area was characterized by general ground warping, ejections, fissuring, severe landslides, and caving of stream banks. Johnson and Schweig attributed this earthquake to a rupture on the New Madrid North Fault. This may have placed strain on the Reelfoot Fault.

- February 7, 1812, 09.45 UTC (3:45 a.m.); (M 7,5 -8,0) epicenter near New Madrid, Missouri. New Madrid was destroyed. In St. Louis, Missouri, many houses were severely damaged, and their chimneys were toppled. This shock was definitively attributed to the Reelfoot Fault by Johnston and Schweig. Uplift along a segment of this reverse fault created temporary waterfalls on the Mississippi at Kentucky Bend, created waves that propagated upstream, and caused the formation of Reelfoot Lake by obstructing streams in what is now Lake County, Tennessee.

Eyewitness accounts

After supper, we went to sleep as usual: about ten o'clock, and in the night I was awakened by the most tremendous noise, accompanied by an agitation of the boat so violent, that it appeared in danger of upsetting ... I could distinctly see the river as if agitated by a storm; and although the noise was inconceivably loud and terrific, I could distinctly hear the crash of falling trees, and the screaming of the wild fowl on the river, but found that the boat was still safe at her moorings.

By the time we could get to our fire, which was on a large flag in the stern of the boat, the shock had ceased; but immediately the perpendicular banks, both above and below us, began to fall into the river in such vast masses, as nearly to sink our boat by the swell they occasioned ... At day-light we had counted twenty-seven shocks.

On the 16th of December, 1811, about two o'clock, a.m., we were visited by a violent shock of an earthquake, accompanied by a very awful noise resembling loud but distant thunder, but more hoarse and vibrating, which was followed in a few minutes by the complete saturation of the atmosphere, with sulphurious vapor, causing total darkness. The screams of the affrighted inhabitants running to and fro, not knowing where to go, or what to do—the cries of the fowls and beasts of every species—the cracking of trees falling, and the roaring of the Mississippi— the current of which was retrograde for a few minutes, owing as is supposed, to an irruption in its bed— formed a scene truly horrible.

On the night of 16th November [sic], 1811, an earthquake occurred, that produced great consternation amongst the people. The centre of the violence was in New Madrid, Missouri, but the whole valley of the Mississippi was violently agitated. Our family all were sleeping in a log cabin, and my father leaped out of bed crying aloud "the Indians are on the house" ... We laughed at the mistake of my father, but soon found out it was worse than the Indians. Not one in the family knew at the time that it was an earthquake. The next morning another shock made us acquainted with it, so we decided it was an earthquake. The cattle came running home bellowing with fear, and all animals were terribly alarmed on the occasion. Our house cracked and quivered, so we were fearful it would fall to the ground. In the American Bottom many chimneys were thrown down, and the church bell in Cahokia sounded by the agitation of the building. It is said the shock of an earthquake was felt in Kaskaskia in 1804, but I did not perceive it. The shocks continued for years in Illinois, and some have experienced it this year, 1855.